What We Ride

You don’t get much sympathy from your riding buddies when you complain, “I have to ride another review bike,” and you’re pedaling some shiny new bit of steel. It’s true that when pondering a list of dream jobs, riding new bikes for a living is pretty high up for any real cycling nerd.

But for many riders — the people behind Adventure Cyclist magazine included — researching, debating, comparing, and finally building the right bike for you is all part of the fun. That’s why, on a perfectly sunny spring day astride some brand-new, well-tuned machine that I get paid to ride the wheels off of, sometimes all I can think is, “I want to ride my bike.”

Besides, if bike builds say something about the rider, then a parts list is more than a spreadsheet — it’s a little glimpse into a cyclist’s strengths and weaknesses, likes and dislikes, maybe even blind spots and biases. Here then are the bikes of Adventure Cyclist, the daily drivers and purpose-built machines that we assembled away from the office, with our own money, and continue tweaking in a constant state of evolution as we look for the same thing every cyclist is always searching for: the perfect bicycle. –Alex Strickland

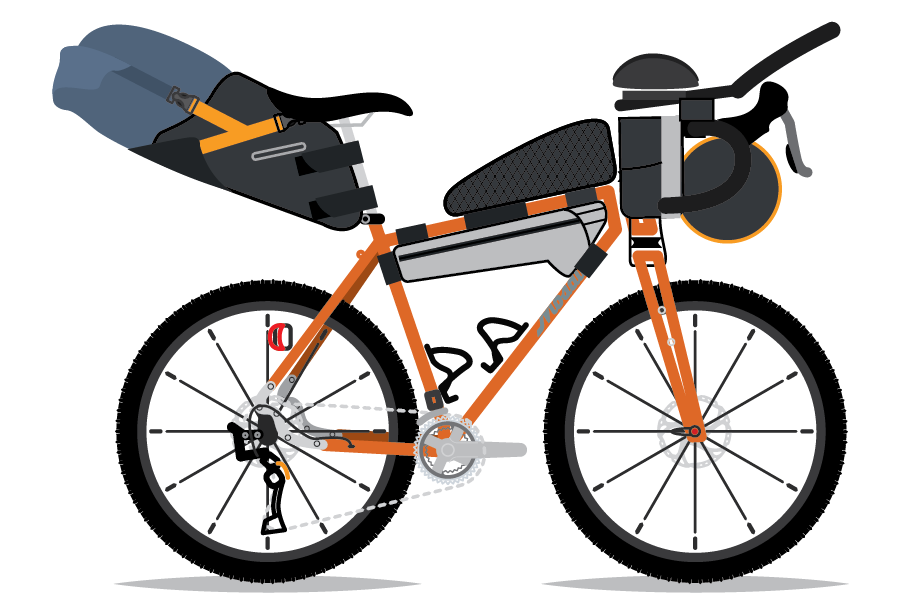

Editor-in-Chief Alex Strickland

Soma Wolverine – somafab.com

There’s an argument to be made that because actions speak louder than words, my “favorite” restaurant is the one I dine at most often. By this logic, my favorite eatery is … not very good. And while I profess more love for other bikes, it’s my trusty (and increasingly rusty) Soma Wolverine that I ride the most. Favorite then? Kind of.

My orange Wolverine has worn a few different setups as it also serves as my primary test mule for reviewing products that appear in Adventure Cyclist. But the relatively stable highlights include SRAM Apex shifters, a 10-speed 11–32T SRAM cassette, Salsa Cowbell bars, Thompson post, and TRP Spyre disc brakes. Outside of those components, the bike has seen some considerable changes over the three years I’ve owned it — more on those below — but first, about that usage. The Soma is my primary commuter year-round, which means it’s subjected to all sorts of weather and four full months of de-icer laid down by the city of Missoula in a failed effort to battle winter’s ice buildup. It’s nasty stuff, and it’s starting to show. The Wolverine lives on a covered porch at home and in Adventure Cycling’s courtyard in a relatively dry climate, but still, rust is a reality for drivetrain parts and even worse for bolts holding the Paragon sliding dropouts and seatstay break for a belt drive. In addition to the daily banging of a life as a commuter, the bike functions as a Montana Road Bike, which is to say that tarmac, gravel, and moments of friskiness on singletrack are de rigueur. All in, the Soma sees about a thousand miles a year, primarily in short bursts.

The Soma’s biggest character shift has come from the wheels and tires it rolls on. After running 700c wheels with 40mm tires for more than a year, I swapped on some 27.5in. (650b) wheels with WTB’s 47mm Horizon “Road Plus” tires. The change was staggering. In fairness, the smaller wheels were also a little higher end, tubeless, and sporting thru-axles instead of quick releases (a benefit of the Paragon sliders was an easy swap to accommodate the new axle), but the bike’s personality completely shifted once the tanwall tires were mounted. Somehow the Soma felt simultaneously sharper and more comfortable. In fairness, the Horizons’ smooth design is entirely worthless once the snow flies, so 42mm Surly Knards go on for winter. Suffice it to say that by late February I’m looking at 10-day forecasts to figure out how soon I can mount up the Horizons again.

The last major change is a carbon fiber fork from Fyxation. The stock lugged steel fork (in matching orange) looks classic and features traditional mounts but was much too flexy — you could watch the front wheel dive beneath you as you shuddered to a stop. The Sparta has slightly less trail, which has sharpened the bike more than some might like, but it’s also stiffened up the front considerably. It’s not especially light for a carbon fork (credit the alloy steerer tube and alloy inserts in the fork legs to back the three-pack mounts), but it appears to be the only carbon option on the market with a straight steerer tube. It also sports a 12mm thru-axle, which requires the use of an adaptor with my 15mm mountain wheel (I also used an adaptor for the front wheel when running it with the stock fork). Soma does offer a unicrown steel fork for the Wolverine as an aftermarket option complete with a 15mm axle and matching colors, but for $80 more I’d go with the Fyxation.

So what’s next for my trusty rusty? As mentioned above, the frame features a break in the seatstay for a belt drive, and I’ve strongly considered running a singlespeed belt during the winter months to combat corrosion. A Shimano Alfine internal geared hub also holds some allure, though I’m not sure I’d appreciate the weight once the pavement ends, and it would demand changing my well-liked SRAM levers.

Familiarity may breed a bit of contempt with my Wolverine, but the fact of the matter is that I ride this bike every day. It’s done everything I’ve asked and more while receiving some brutal treatment at the hands of Montana’s long winters and a lazy mechanic. Hard to argue with that.

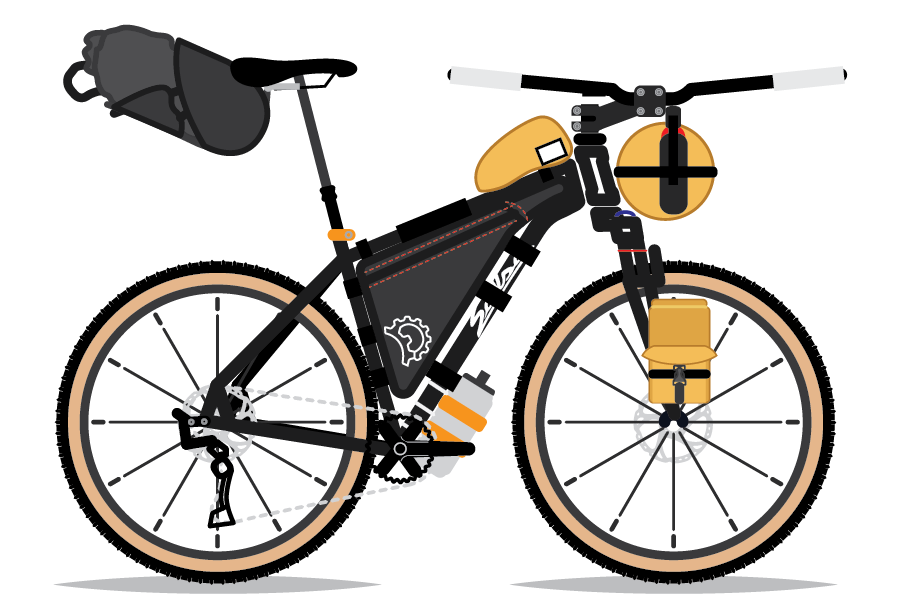

Staff Writer Dan Meyer

Salsa El Mariachi – salsacycles.com

I somehow got it in my head that I needed a new mountain bike, preferably one with 29in. wheels, one gear, no suspension, and a frame made of steel. Lucky for me the last remaining Salsa El Mariachi SS models were on closeout, so I bought one, size large. It was a steal.

Nota bene: the El Mariachi perfectly illustrates the fact that steel doesn’t have to be heavy, or that lightweight steel needs to be expensive.

My new El Mariachi brought me back to the old days of bumping painfully down the trail, my hands going numb and a smile broadening across my face. Riding rigid and singlespeed retaught me how to maintain momentum and pick smooth lines. Every ride was a master class in bike handling. I loved it.

Helga the Boneshaker, Gatekeeper to the Pain Cave (or just Helga if you’re into the whole brevity thing), came from the factory with serviceable parts, but I replaced most everything. I gave her a carbon bar, Thomson bits, bigger brake rotors, and — most important — high-quality, handbuilt wheels. If the shoes make the man, then the wheels make the bike. (Me? I wear slippers.)

With new parts all around, Helga was a light, strong, and still pain-inducing singletrack weapon. But there was one thing that Helga wasn’t very good at — bikepacking. It took two seasons for me to realize that singlespeed bikepacking is dumb. I needed gears. And a suspension fork. And a dropper post. And better brakes.

I considered keeping Helga as-is and buying a whole ’nother bike, but in the end I decided that the El Mariachi is a great bikepacking platform and I’d be doing Helga a disservice by preventing her from living up to her potential. So on went a 100mm Rockshox Reba, a dropper seatpost (internally routed on a frame without internal routing, but that’s a story for another time), a new rear wheel, and a full Shimano XT group with an 11–46T cassette. Only two parts remain on the El Mariachi that came from the factory: the seatpost clamp and the headset.

After the hardgoods came the softgoods: a large Revelate Designs Ranger framebag filled the front triangle, a Porcelain Rocket Albert seatbag bolted to the saddle rails, either a Revelate Harness or Sweetroll strapped to the handlebar, and Outer Shell Adventure’s excellent Pico Panniers clamped to the fork legs. I also attached King Cage’s titanium Many Things Cage to the down tube using King’s own Universal Support Bolts.

Bikepacking is many things to many people, and because I have a day job, bikepacking for me is overnights and weekend trips. I’m not about to ride the length of South America on dirt roads — if I were, I’d consider a different machine, or at least a different setup on this one. But for riding to our local camping spots outside of town, shredding singletrack after a night in the woods, or just riding trails unloaded, Helga is exactly how I want her to be: smooth and stable, but ready for fun.

My beloved El Mariachi is a very different beast than when I bought her. No longer a stripped-down singlespeed pain machine, Helga nevertheless feels like the same bike — sharp angles, slender steel tubes, and classic looks. A few gears and a bit of buttery suspension can only change a bike so much.

I sometimes miss having a singlespeed. But then again, I sometimes don’t.

Postscript: When I bought it, I had no idea that 2015 would be the last year Salsa offered a singlespeed El Mariachi, or that 2016 would be the final year of the El Mariachi altogether. No longer would Salsa make a classic steel hardtail. I bought a piece of history, and I didn’t even know it. It was providence.

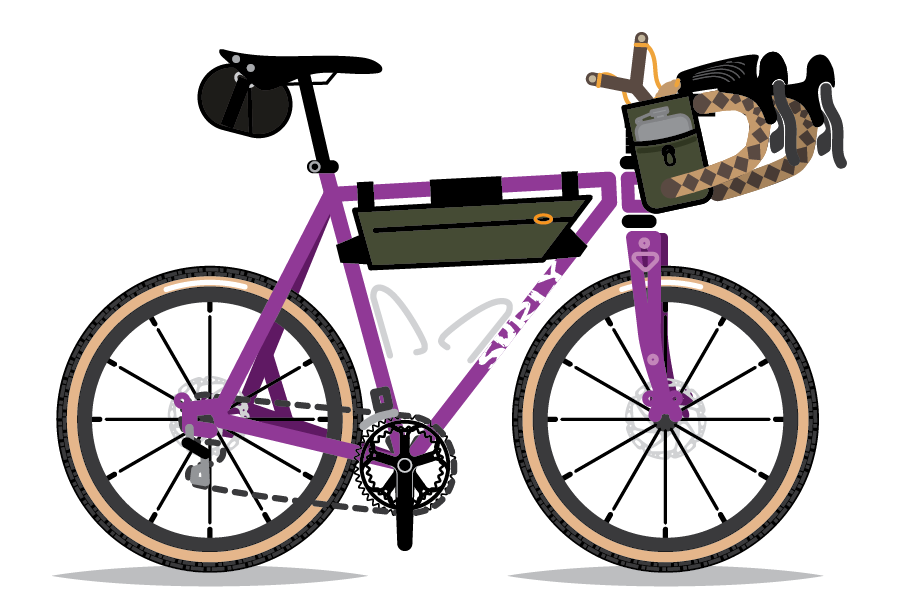

Lead Designer Ally Mabry

Surly Straggler – surlybikes.com

I first placed my finger to the off-road touring pulse in 2015 when I lived in Austin, Texas — about the same time Ultraromance graced the cover of Bicycling Magazine and when Instagram was only on the cusp of being saturated with golden-hued photos of touring rigs backed by dreamy gravel roads. I drooled over gravel bikepacking routes in between completing projects in my graphic design day job.

In anticipation of my first proper bike tour, I built my first nonstock bike from the ground up: a 2013 Surly Straggler. Thanks to some eBay luck, the frame already had an impressive touring résumé: turns out it was Sarah Swallow’s first gravel rig. It even came with a custom Porcelain Rocket framebag.

The only brand-new components on my build were a Brooks saddle, cassette, chain, and TRP Spyre disc brakes. Everything else was hunted on eBay or scavenged from my friend’s random parts bin. Up until very recently, I was running mismatched SRAM Red and Rival 10-speed shifters.

Buying mostly used parts allowed me to build a much higher-quality machine than if I’d bought a complete bike from a manufacturer. I’d never built a bike from scratch, and because I planned to tour remote areas with this one, I wanted to feel as comfortable as possible with the mechanics. Assembling it myself was invaluable.

The result is a seemingly modest steel steed that I know like the back of my hand. Named Merlin for its glittery purple paint, riding this bike is so smooth it feels like magic. With Merlin I’ve toured the length of Oregon, the washed-out backroads of Arkansas, and up and down the fire roads of Montana. I often commute and I occasionally race on it. I learned how to ride singletrack on Merlin, often being the only woman on a ’cross rig at the mountain bike park in Austin. The bike handles it all.

If I had to get rid of every bike in my quiver and keep one, Merlin would stay. It’s my everything bike—not only did I pour an incalculable amount of love into the build, but it quite literally is built for almost everything (except fatbiking).

Merlin has been everything I’ve needed in a bike for the past three years, and it definitely shows. As the components begin to wear out, I’ve started the slow journey of upgrading. The mismatched shifters have been replaced with 11-speed SRAM Rival 22s, which means I’m eventually due for a new rear derailer and 11-speed cassette (I don’t mind the extra click for now, and neither does my bank account). I’ve taken it upon myself to master the painfully tedious art of Harlequin handlebar wraps, so I’m sure I’ll be going through a lot of Newbaum’s as well. One thing’s for certain: no matter how many components change, Merlin will continue to be my go-to bike.

Technical Editor Nick Legan

Mosaic Custom – mosaiccycles.com

The evolution of the bikes I use for bikepacking has been an interesting process. It started with a borrowed Salsa Spearfish, a cross-country, dual-suspension mountain bike. After a great trip in Utah’s Wasatch range, I moved on to a Ragley TD1, a now-discontinued titanium 29er. It was replaced by yet another Salsa, a titanium El Mariachi. So far all my bikepacking rides used a flat bar. Next up was a custom randonneur bike by Harvey Cycle Works that had extra tire clearance for 650b x 2.1in. tires.

While all of those bikes worked well for a very specific type of riding, for my next bike I wanted something more versatile. Dropbars keep my hands happy. Wide 29er tires give me comfort and traction. A rigid bike keeps maintenance to a minimum. When Salsa’s Cutthroat came onto the scene, I told my wife, “That’s my next bike.” After riding a Cutthroat, I knew that its dropbar 29er geometry was for me.

But as a fan of steel bikes and threaded bottom brackets, the Cutthroat didn’t actually tick all my boxes. So instead of ordering one, I gave my friend Aaron Barcheck of Mosaic Cycles a call. He works predominantly in titanium road bikes. So my bike is a departure from the norm for Mosaic, but Barcheck’s ability to realize an idea whatever its form is beyond reproach.

While we based the geometry on Salsa’s Cutthroat as a starting point (the fork is a carbon Salsa Firestarter model painted to match), we did make a few changes. We lengthened the top tube to accommodate my monkey arms and carefully positioned the cages so they would clear one-liter bottles. We also dropped the top tube, using more exposed seatpost so that I could run a dropper post in the future if I wanted to.

We also made sure that I could use 29er mountain bike wheels as well as 27.5in. (or 650b) wheels with plus-sized, 3in.–wide tires. I’ve also ridden the Mosaic with 700c x 40mm tires at several gravel events.

Whether it’s a quick overnighter on tap or a weeklong adventure, the Mosaic is my go-to adventure bicycle. I couldn’t be happier with the way it rides, how it fits, and I love the look as well.

Road Tester Patrick O’Grady

Voodoo Nakisi – voodoocycles.com

It’s true that I own a ridiculous number of bicycles.

It is not true that my wife had to get a better job in Albuquerque so we could afford a bigger house with a two-car garage, though it may be said that our two-bedroom, one-car place in Colorado Springs always seemed full of bikes for some reason.

And yes, here in the Duke City we can park cars in the garage, not just bicycles, and move through it and the house without hooking a sleeve, pocket, or purse on a handlebar.

Well, sometimes, anyway.

Aristotle postulated that nature abhors a vacuum. I have deduced further that these voids attract bicycles. At the moment I count 15 in the garage and five in the house.

Two are review models, but still, any more and we’ll need a bigger void.

It was not always thus. There was a time when we didn’t have a garage of any sort. In those dark days I limited myself to a road bike, a mountain bike, a time-trial bike and two cyclocross bikes, because any ’cross racer who didn’t have a pit bike hadn’t fully committed to the discipline.

Okay, so I had three ’cross bikes and had been caught using our bathroom shower as a post-race power wash. My wife considered having me committed, and not to the discipline, either.

Today I have six, three of which overlap with that nebulous category dubbed “all-road,” “gravel,” or “adventure.”

The one I reach for most often is a dusty, scarred Voodoo Nakisi. It debuted as a $399 black-and-silver chromoly frame and fork in 2009, but I didn’t get mine until a year later.

At the time I was riding a Steelman Eurocross everywhere, the ’cross bike being the original gravel bike.

But limited to what then was a fairly traditional setup — 700c x 32mm tires, 48/36T chainrings, and an eight-speed, 11–28T cassette — my resistible force would eventually meet some immovable object and I would find myself afoot, shambling along a pesky stretch of singletrack that would be child’s play for a fat-tired, broadly geared mountain bike.

You may recall that I mentioned owning one of those. But it was basically a garage-based automobile repellent, because I rarely “mountain biked.” What I did was ride a bike, wherever, and right out the front door, too. If I felt like veering off pavement onto some seductive trail, I did it.

I just wanted to be able to stay in the saddle. Walking is so … pedestrian.

Thus the Voodoo Nakisi. Casual observers have mistaken it for a cyclocross bike based on its dropbar and plump knobbies, but it’s actually a monster-’crosser, a rigid 29er, with the capacity for 2.3in. rubber.

Out of the box the Nakisi could be all things to all people. Rim brakes or discs, singlespeed or geared, fat tires or thin, flat bar or drop; you could even add fenders and racks if you liked.

As designer Joe Murray told the blog Cycloculture in 2012: “It turned out to be a great commuter as well as a dirt-road cruiser … an all-around bike.”

Some aesthetes derided the high-rise stem, mandated by the Nakisi’s short head tube and nearly flat top tube, which Voodoo’s John Benson told me were intended “to offer a traditional look with lots of standover clearance.”

“That has met a fair amount of resistance, especially when the high-rise Nakisi stem is put on,” he conceded. “It does look goofy, but man, it is great riding that setup.”

Benson wasn’t just spreading the ol’ marketing margarine. That goofy setup gave me a bird’s-eye view of the trail ahead — especially since I added top-mounted brake levers to the drop bar — and I instantly appreciated the standover clearance when riding beyond my negligible abilities.

Dropbar? Yep, a wide Salsa Pro Road. I went the monster-’crosser route because I had a bunch of suitable parts scattered around my bike shop. Garage. Whatever. That handlebar, some beat-up aero brake levers, cantilever brakes, a prehistoric Shimano triple crank with a steel 22T granny ring, Ultegra rear derailer, Thomson seatpost, Selle San Marco saddle, pedals, and so on and so forth.

A few items had to be scrounged or bought — a SRAM nine-speed road cassette and chain, XT front derailer, Dura-Ace bar-cons, and wheels.

I eventually replaced the San Marco with a Selle Italia that didn’t keep a death grip on my shorts. Likewise I experimented with pedals (Crank Brothers, Time ATAC) and tires (Panaracer Fire Cross, WTB All Terrainasaurus) before settling on SPDs and Bruce Gordon Rock n’ Roads, which the astronauts did not take to the moon but should have. They don’t make much noise on pavement and hook up marvelously in the Southwestern grit.

Thus equipped, the bike is a simple, field-repairable all-terrain vehicle. It starts, goes, and stops via mechanical levers and cables. There are tubes in the tires. The only suspension is of disbelief.

Its gearing, forced upon me by frugality and happenstance, is low enough to tackle most of the singletrack climbs in my neck of the cacti. And once over the top and careening down the other side, the Cane Creek SCX-5 cantis with Kool-Stop pads have proven superb, reminding me of the late, lamented Dia-Compe 986.

My Frankenbike and I have startled hapless villagers on singletrack, doubletrack, and seemingly endless gravel climbs in Colorado, on spiky, rocky trails in Arizona and New Mexico, and even on the paved bits between dirty business. If I’m on a quest and need One Bike to Rule Them All, this is it.

In Albuquerque a typical outing starts and ends with a few lazy minutes on suburban streets followed by a couple hours scampering around the roller-coaster trails lacing the foothills of the Sandia Mountains. The marked routes are pretty tame, and I can ride them on an actual cyclocross bike, but they’re so much more enjoyable on the Nakisi.

There are a few things it can’t do, and a few things I can’t do, and happily they coincide, so we rarely embarrass each other. Though recently we did stuff it into some trailside cane cholla on a loose, narrow descent. I blame myself. The mind, it wanders, and just when it shouldn’t, too.

After nearly eight years, I’ve nearly ridden the wheels off this thing, and so I’ve ordered replacements from Rich Lesnik, the wheelbuilder for Rivendell Bicycle Works. With their wider Velocity Cliffhanger rims I should be able to bring more rubber at lower pressure to that tricky drop.

I confess a temptation toward further renovation: maybe a bar with a little less reach and drop; perhaps a Deore rear derailer and 11–34T cassette for really steep pitches; Paul’s MiniMotos for greater stopping power, and … and …

And probably not. As it stands, the Voodoo Nakisi lets me expand my universe without deluding me into thinking I am its master. We’re such a perfect fit that I’m reluctant to start waving my wand at it. What happens if I muck up that ol’ black magic?

I don’t want to undo the Voodoo that I do so well.

Like the illustrations in this piece? We do too. Check out all of Mr. Crumbs’ work at bicyclecrumbs.com or follow along @bicyclecrumbs.

A version of this feature originally appeared in the August/September 2018 issue of Adventure Cyclist magazine.