The Middle of Nowhere is in Eastern Nevada

This article first appeared in the November/December 2023 issue of Adventure Cyclist magazine.

It was only Day One, and we’d already found ourselves in a grim state of affairs. Our route had deteriorated from a pristine gravel road to a rarely traveled doubletrack with the occasional sandy patch to the scant path on which we now pushed our bikes. This trail might once have been passable on two wheels, but it appeared that runoff from this year’s massive snowpack had erased it from the face of the earth. We could occasionally hop on our bikes and pedal for 50, 60 feet, if we were lucky, but mostly we dragged our loaded rigs through fine sand several inches deep, and had been doing so for miles.

There was no alternate road, and turning around wasn’t an option. There wasn’t anything out there anyway, no salvation. We were in the actual middle of nowhere, in eastern Nevada, attempting a three-day circumnavigation of Great Basin National Park. We hadn’t seen a lot of people since leaving Ely that morning. We’d last seen another human — an older guy driving a bombed-out truck who pointed out a herd of elk to us on the side of the road — hours ago.

Evan and I hadn’t said a word to each other since we started pushing our bikes. We were in unspoken agreement that 1) we preferred to sit alone in our respective pain caves, and 2) it was entirely possible that we could be approaching real danger. There wasn’t any utility in complaining about the sand, or whining about how tired we were after riding for eight hours, or fretting about our diminishing water resources and the utter lack of the wet stuff along this part of the route. But as Evan pushed his bike onto supportable dirt and swung his leg over the top tube and got a few pedal strokes in, only to grunt in frustration as his rear tire fishtailed in the sand and he again hopped off the bike and dropped his head and began to push — and I followed the same pattern a few bike lengths behind him — he glanced back and we locked eyes for a moment, telepathically agreeing that our planned campsite, marked as Indian Springs on all the maps we’d consulted, absolutely had to have water. The light coming through the ponderosa was beginning to change; evening would soon be upon us.

As we topped out on the “road,” I felt a small wave of hope: we were done climbing, and the descent before us consisted not of sand but of loose rocks. It was rideable, at least. And despite the report of zero percent chance of storms we’d gotten from Evan’s satellite device, a few drops of rain kissed my cheek.

After crossing several more washed-out sections of road, we rounded a corner and came upon what could only have been a mirage. For hours we’d been riding through a brown and gray desert populated with pale, greenish-blue sagebrush, juniper trees, and ponderosa pine. Suddenly the landscape erupted in vivid, almost cartoonishly green shrubbery. It was like seeing color for the first time, and it was so shocking that it didn’t register with us at first. We split up to seek out water. I followed the road up a gradual ascent as Evan went the opposite direction. The road quickly turned to sand again. I pushed my bike for a few minutes before letting it fall to the ground and abandoning it. I figured I could cover more ground without it. After stepping off the road to look for any sign of a spring, I heard a shout. Turning around, I saw Evan on top of a boulder the size of a small bus, waving his arms and yelling excitedly. I quickly ran back to my bike and rode down to where I’d seen him. The road became engulfed in waist-high grasses and I rode through — was that mud? I came to a stop to call for Evan, and then I heard it: a babbling creek and buzzing insects. Water!

It was cold, clear, and plentiful. We filtered, filled our bottles, splashed our faces, and washed dirt from our arms and legs. Evan found a spot deep enough to shove his entire head into the creek; I followed suit thereafter, ignoring the two beetles mating on a nearby rock. Not a hundred feet from the creek was a perfect desert campsite: a flat-ish stretch of dirt enclosed by boulders and a few large juniper trees. We weren’t the first ones to camp here. In fact, we’d been following tire tracks from a single dirt bike for miles. That person must have camped here too. But no sign of pedal bikes. In fact, we didn’t see any other cyclists on our route at all, which isn’t surprising given how remote this area is. We might have been the first bikepackers at this campsite.

As the sun set behind the mountains, we could see the valley unfurl to the east and glimpse the road we’d tackle in the morning. Two parallel straight lines, a doubletrack road, jutted all the way to the horizon and would take us to the southern edge of Great Basin National Park. We hoped — prayed — that it would be rideable. If it consisted of deep, unsupportable sand? That was tomorrow’s problem. For now, we set up our tents and cooked our dinners, grateful to end the first day of our trip on a high note.

Ely is a town of about 4,000 people in the mountains of eastern Nevada. Founded as a stagecoach station on the Pony Express Route, the discovery of copper in 1906 led to rapid growth and, like so many other towns in the Mountain West, a series of booms and busts. Visitors can experience the town’s history at the Ely Renaissance Village, an open-air museum, and by admiring the many murals on the sides of buildings downtown.

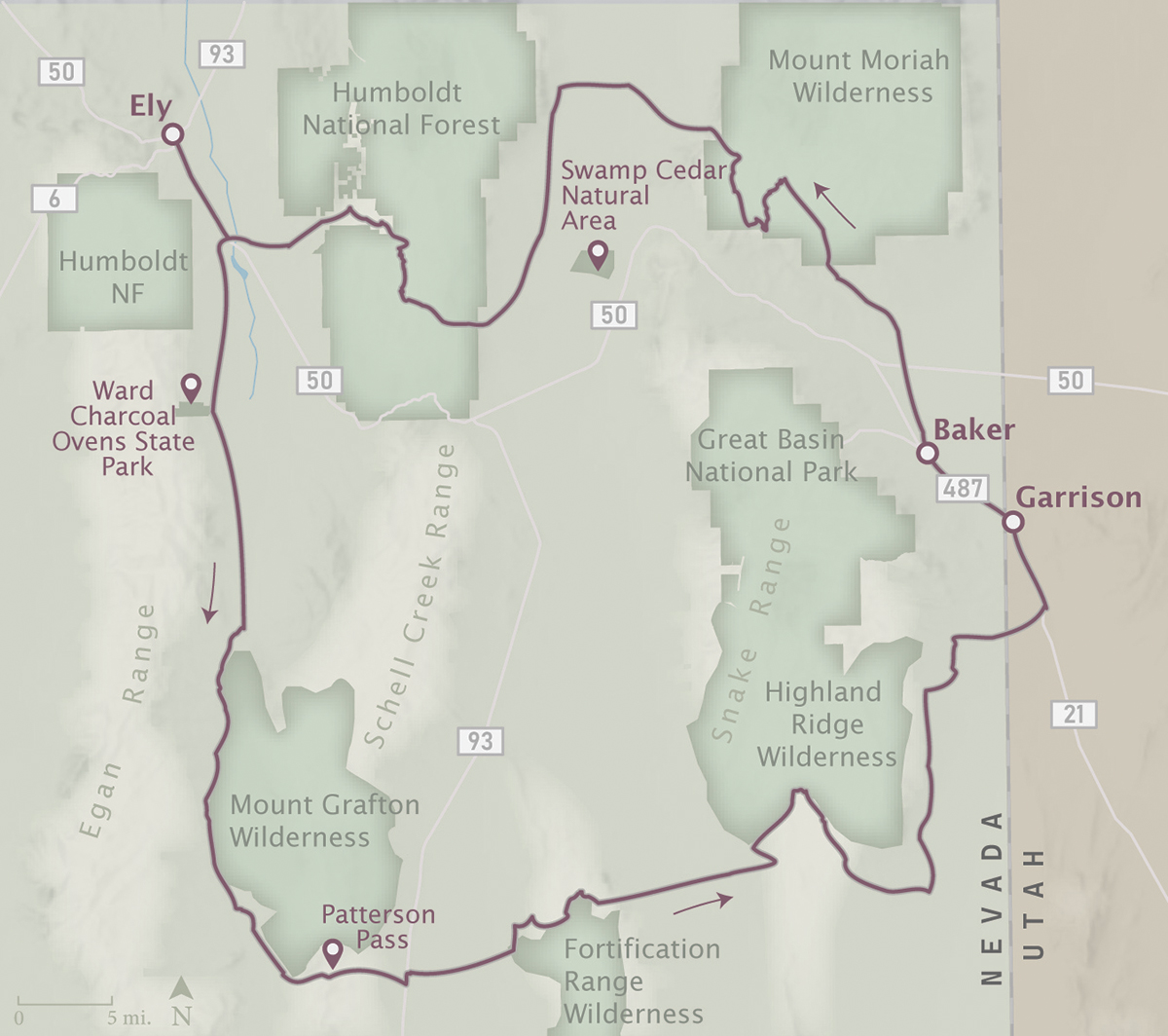

Kyle Horvath, the director of tourism for White Pine County, Nevada, invited me to come check out Ely and experience the potential eastern Nevada has for bikepacking. Kyle has been mapping local routes on his own and hopes to put Ely on the map as a future bikepacking destination. He sent me a collection of GPX tracks he’d put together — some of which he’d put tire to dirt, some he hadn’t — and I pieced together a three-day route I began to informally call the Great Basin South Loop. We would start and finish in Ely and traverse an entertaining collection of desert ecosystems, climb a few mountain passes, and stop for a night in the tiny town of Baker for a dose of civilization. In short, I hoped to get a lot of bang for my buck in three days’ time.

Kyle had hoped to join me, but we both had busy summer schedules and our original plan of setting off in May was dashed by the stubborn snowpack. I didn’t want to be pushing my bike through enormous snowdrifts. I landed on the final week of June as the only week available, but Kyle would be out of town filming a local athlete in the Race Across America. Luckily, I found a buddy to come with me.

Not long after I moved to Salt Lake City in the summer of 2020, I met Evan on an overnighter set up by our local shop, Saturday Cycles. We were both military veterans (I was a grease monkey in the Marines; he worked on nuclear submarines in the Navy) and we became fast friends. It helped that we were both a little older than the others and rode at a similar pace. We spent the next few summers riding bikes in the summer and snowboarding in the winter, and after he completed his PhD in the spring of 2023, he was offered a job he couldn’t refuse: teaching electrical engineering at the University of Utah’s Asia Campus in Seoul, South Korea, for two years. It was obvious what had to happen next: a going-away bikepacking trip.

Thankfully, Day Two was mostly uneventful. We saw a herd of pronghorn and got our first glimpse of the snowy peaks of Great Basin National Park as we neared the tiny town of Baker, where we spent the night. Note to those looking to replicate our route: plan for a layover day in Baker.

Day Three was bound to be a doozy. Completing our loop back to Ely would see us crossing not one but two mountain ranges, the Snakes north of Baker and the Schells to the west. Luckily, we had an ace in the hole: if we got into trouble, we could summon help from Kyle via Evan’s Garmin satellite device. I for one wasn’t above asking for a ride if we really needed it.

Our first surprise came at the southern edge of the Snake Mountains as we forded our bikes across a healthy-looking creek. Not knowing what was in store, we stopped to remove our shoes and socks before the crossing and then took the time to clean and dry our feet before putting them back on. Within a few minutes of pedaling, we came to another creek crossing. And then another. Our route crossed Silver Creek over and over again, to the point that, to save time and effort, Evan decided to just get his shoes wet and I switched to sandals.

Up and up we labored, following the creek and riding through increasingly lush zones. As we gained elevation, we came upon bristlecone pine trees and wildflowers. Finally, the drainage we were following opened up into a convergence where the different forks of Silver Creek merged to form the body of water we’d spent all morning crossing. We were maybe a quarter of the way into our day’s mileage, and we could see that the road ahead was so steep we’d be pushing our bikes. Moreover, some weather was forming above Mt. Moriah to the north and looked to be heading our way. We had no time for equivocation.

There exist different flavors of bike pushing, and I’ll take hauling a loaded bike up a steep road on a firm dirt surface any day over heaving my rig through several inches of moon dust. Luckily, the pushing was over before we knew it, and the weather seemed to be holding off. We dropped over the ridge and followed a steep descent deep into a hot, dry canyon — the opposite of the zone we’d just left. There followed a long climb up a very consistent grade, so consistent as to drive you mad. The pitch never eased up to give us a break, but at least we found some level of distraction in the changing temperature and available wildflowers as we gained elevation. The lupine turned from blue to purplish as we gained the ridge.

As we found ourselves on a plateau with a view of the gorgeous Spring Valley to our west, we took the opportunity to have a break and check in with each other. It had been a long day: we’d climbed over 5,000 feet and still had another 30 miles and 3,000 feet to go before reaching Ely, and it was getting late. It was nearly 5:00 PM. Neither of us had a strong desire to roll into town in the dark, with all the restaurants closed (food being front of mind at this point in the journey), and finding a place to camp for the night and finishing the route the following day wasn’t ideal. We both had stuff to get home to, and sooner rather than later.

Another option we discussed was scrapping the last part of the route and riding pavement back to Ely. It would be a little quicker, but the thought of pedaling 30 miles on a high-speed, two-lane highway with no shoulder as the sun went down made me a little nauseous.

Finally, we agreed to swallow our collective pride and call for help. I actually had signal for once, so I messaged Kyle to let him know our situation and ask for a pickup. The last section of the route would have to wait for another time.

After confirming the message was sent, we geared up and began the harrowing descent into Spring Valley. Following Evan, it became immediately clear to me that this was going to be steep and fast. The road hooked around a quick S-bend abloom with flowers and then pitched straight down into the steepest road I have ever seen in my life. I was reminded of riding roller coasters as a kid — ratcheting slowly to the edge and, for a moment, hanging midair, my organs pressed against my ribcage, people on the ground like insects, and hearing vanishing screams from the seats in front of me before I too plummet to the earth. This wasn’t a road; it was a waterfall made of rocks and dirt; it was falling off the face of the planet.

I crashed. I went over the bars and landed ungracefully, but luck was on my side: other than a few scrapes, I was fine, and the bike came out unscathed. I’m not afraid to say I walked for a little bit after that until I could regain some courage.

Before long the road settled into a sane gradient, and we cruised out of the mountains and into the broad expanse of Spring Valley. Crepuscular rays broke through the clouds, highlighting the dust rising and dissipating from a vehicle in the distance. Before us lay verdant green fields and farmhouses, roads like a T-square, and the Schell Mountains still frosted with the winter’s heavy snowpack and backlit from the setting sun. Evan was a mile ahead of me, a speck, but I could hear him hooting with joy.

After I caught up with him, we rode side by side, hunting for a washboard-free track in the dirt road and remarking on the sine wave of emotion that is bikepacking. Especially on a tough loop like this one, in which we’re researching the route and are quite possibly the first bikepackers on some of these roads, the lows can get pretty low, but then we find ourselves pedaling across one of the most beautiful valleys in recent memory and all the things that brought us down and made us question why we pedal overheavy bikes into the hills in the first place — crashes, pushing through sandy washes, knee pain — are transmuted into hilarious remember-whens, as if we’ve developed instant (and highly selective) amnesia.

We hadn’t gotten a response from Kyle — no signal down here — but as we approached the western edge of the valley and the paved road that would take us back to Ely, we saw a truck pull off the macadam and come to a halt in the dirt. No one got out. Could it be Kyle? we asked each other. Had our salvation arrived, possibly with snacks? It was only a half-mile or so away, but it seemed to take forever to get there. Finally, someone got out of the truck and stood there, watching us as we pedaled closer.

I stood to pedal up the short rise to the truck and about fell off my bike from exhaustion as I came to a stop.

“Kyle?”

Evan and I are sitting at a table overlooking the smoky Copper Queen Casino at the Ramada. We had waltzed into the Smash N Grab restaurant (nee Evah’s) just moments before closing time; I might feel bad were I less famished. Our server seems cheery though. She brings us ice water as we gaze at our menus.

Kyle (yes, it was him at the truck) is a true Trail Angel. He and his brother picked us up and gave us Peanut M&Ms and Powerade as we motored back to Ely. We thanked him profusely and lamented our failure to complete the loop, but he was just happy we’d given the route a shot. Evan and I tried to explain how much we enjoyed the route, which sections were rideable and which weren’t, but it was hard to explain in a moving vehicle. We would have an official debrief the following morning over breakfast at the Prospector Hotel and Gambling Hall.

Evan and I had been dying for cheeseburgers, and Kyle had promised that Smash N Grab served the best burger in Ely. So after checking into our hotel and showering up, we dragged our tired legs down the street to the Ramada.

After ordering our burgers, our server asks if we’d like anything else. “I’ll have a scoop of ice cream,” Evan says. The server asks if he’d like her to bring it out when he’s finished with his burger. “No,” he says, “I’d like it as my appetizer.”

This man is a genius! I tell the server I’ll do the same.

Within moments, we each have a bowl of ice cream before us. I have plain old vanilla, but Evan has birthday cake, which I didn’t even know was a flavor. We eat our ice cream, and it doesn’t even matter that it’s mediocre at best. Evan’s bowl has pieces of actual birthday cake in it.

Spring Valley

Situated between the Schell and Snake mountain ranges, to the east of Ely, Spring Valley is a broad, north–south valley that is so lush, it’s hard to believe that no river feeds into it. Instead, over a hundred springs flow into the valley — hence the name — and feed a water table that is protected by a layer of clay. In the valley grow several plants common to the high desert such as sagebrush, rabbitbrush, greasewood, and the like. But there is one species that stands out: groves of Rocky Mountain juniper, known as swamp cedar locally and Bahsahwahbee in Shoshone, are an ecological oddity. Rocky Mountain juniper trees tend to grow in dry, rocky soil on mountainsides, but these groves are in a valley and fed by groundwater with high salinity. They’re also the only native trees in the entire valley.

The swamp cedars and the surrounding waters are considered sacred to the local Western Shoshone and Goshute Tribes, whose ancestors lived in Spring Valley for thousands of years and used Bahsahwahbee for ceremonial purposes. During the western expansion of white settlers in the nineteenth century, there were three massacres of Native tribes in Spring Valley and at the site of the swamp cedars — two perpetrated by the U.S. Army and one by vigilantes. Since then, the Bahsahwahbee has been considered a sacred memorial site for the massacre victims.

The area encompassing the swamp cedars is now listed on the National Register of Historic Places, and in 2021 the state of Nevada passed a law barring anyone without a permit from cutting down the Rocky Mountain junipers. (At one point there were plans in place to pipe the water from the valley’s aquifer to thirsty Las Vegas, but those plans were canceled in 2020.) The local Shoshone and Goshute Tribes are now pushing to designate the Bahsahwahbee as a national monument.

Great Basin National Park

Great Basin is one of the country’s least-visited national parks, but it’s not for lack of attractions: there are pristine alpine lakes (fed by the only glacier in the state), herds of pronghorn, and, thanks to some of the darkest skies in the U.S., great stargazing. You can pedal the paved road all the way to 10,000 feet (or take the shuttle if your legs are talking to you), park your bike, and hike to the 13,065-foot top of Wheeler Peak, the second-tallest mountain in Nevada. Reserve a tour of the Lehman Caves system and explore the limestone and marble caverns and their stalagmites, stalactites, and … helictites, whatever those are. And let’s not forget the oldest living trees on the planet, bristlecone pines, some of which are thousands of years old. If you’re up for it, you can search for Methuselah, the oldest-known bristlecone at 4,900 years and whose location is a secret. nps.gov/grba/index.htm

Baker

The tiny town of Baker, pop. 400 (seems more like 40), is the gateway to Great Basin National Park. You won’t find any luxury resorts or condos in Baker, but you will find all the amenities a bike traveler needs, such as indoor lodging, camping, a couple of restaurants, a general store, and a post office. If I were to repeat this trip, I would plan for a layover day or two in Baker to take advantage of the park and to spend more time petting the shop cats at the Bristlecone General Store. travelnevada.com/cities/baker

Nuts & Bolts

Eastern Nevada

Getting to Ely

As the desk clerk at the La Quinta informed me, Ely is “four hours from everything.” Fly via any number of airlines into Salt Lake City, Reno, or Las Vegas, and rent a car for — you guessed it — a four-hour drive to Ely.

When to Go

The best times to visit eastern Nevada are spring and fall, with an emphasis on spring for wildflowers and more abundant water from snow runoff.

At an elevation of 6,400 feet, Ely is listed as one of the coldest places in the contiguous U.S. That elevation moderates temperatures during the summer: during our trip in late June, we experienced mostly highs in the 70s, and Kyle assured me that a heat wave for Ely consists of a two-hour period of 92°F. As you get into lower-lying areas, however, expect higher temperatures. Baker, for example, sits about a thousand feet lower than Ely and was a fair bit warmer.

Where to Stay

There’s no shortage of places to stay in Ely, but I highly recommend booking early, as it’s a busy tourist destination. We stayed a night each on either end of our trip at La Quinta; it was clean, offered waffles for breakfast, and we were able to park the car in the grocery store lot next door during the trip.

If you want to stay someplace with a bit of character, there are a number of historical hotels in operation, such as the Hotel Nevada and Gambling Hall (opened in 1929) and the Jailhouse Motel and Casino, both downtown. Note that smoking is allowed in casinos and bars in Nevada, a fact I was reminded of when Evan and I rolled into town and got a beer at the Hotel Nevada.

In Baker, you can find indoor lodging at the Stargazer Inn and tent sites (with showers and laundry) at the Whispering Elms Motel and RV Park.

Eat and Drink

We enjoyed excellent breakfast at Margarita’s in the Prospector Hotel and great burgers at Smash N Grab in the Ramada. If you’re looking for fine dining, check out the Cellblock Steakhouse, where you can eat your dinner inside, yes, a jail cell. There are many other options we didn’t get a chance to try, such as taco shops and sports bars. For groceries, there’s a Ridley’s right next to La Quinta on the south end of town.

In Baker, you’ll find snacks and supplies at the Bristlecone General Store and sit-down meals at Sugar, Salt & Malt.

What Bike

I rode a Black Mountain Cycles La Cabra, a steel dropbar mountain bike, with 2.6in. tires, and I think it was the right bike for the mix of smooth gravel, sandy washes, and rocky descents on our route (look for a full Road Test in a future issue). If you pick another route in the area that sticks to the main gravel roads, you can get away with a more traditional gravel bike with skinnier tires, but even then I wouldn’t go any narrower than 40mm.

What to Do

A quick glance at a map will show you an endless array of gravel roads surrounding Ely and its environs, but don’t forget about your mountain bike: there are singletrack trails too, mostly on Ward Mountain to the south. Train buffs should check out the Nevada Northern Railway Museum, home to the Ghost Train of Old Ely, a working steam train. There’s even an annual race in September, in which participants ride the train to the start and then race it — on dirt or on the road — back to Ely!

Farther afield, you can find fishing, hiking, swimming, and boating at Cave Lake State Park, and be sure to check out Ward Charcoal Ovens State Historic Park, featuring giant charcoal ovens you can walk right into (don’t worry, they’re no longer in use).

Water

To be clear, this is the desert, so drinkable water should be top of mind. We got lucky in that this year’s massive snowpack led to healthy springs and creeks, but that may not be the case every year. Pore over your maps, find snowpack and water data online, and call BLM and Forest Service offices for local beta depending on where you’re planning to ride. If you’re worried about not being able to find water on your route, it’s never a bad idea to drive the route ahead of time and cache water.

There are a lot of cattle, elk, and pronghorn in this part of the country, so be sure to filter or treat any water you find. And keep an eye out for abandoned mines — you don’t want to be drinking anything downhill of mining tailings.

Other Routes

It’s important to note that the ride Evan and I did was partly route research; Kyle hadn’t ridden much of it, and as you can see, we ran out of time to finish it. In retrospect, I would have stretched it out to four days. Kyle has documented other routes starting in or near Ely that are fully vetted, much of them perfect for a short week or a long weekend.

Resources

For more information on riding in Ely and eastern Nevada in general, visit elynevada.net.