Hellbikes on Ice

Like an isolated Galapagos, Fairbanks, Alaska, in the 1980s was a veritable hotbed of thriving mutants who evolved with a suite of novel outdoor skills built on the experience and wisdom of the climbers, canoeists, backpackers, skiers, snowshoers, hunters, and homesteaders who came before them. But by adapting an explosion of new gear to novel techniques, Fairbanks’s adventurers marked the beginning of outdoor pursuits that would spread across the world over the coming decades. One of those would later be called “bikepacking,” but in the 1980s three of us called it “hellbiking.”

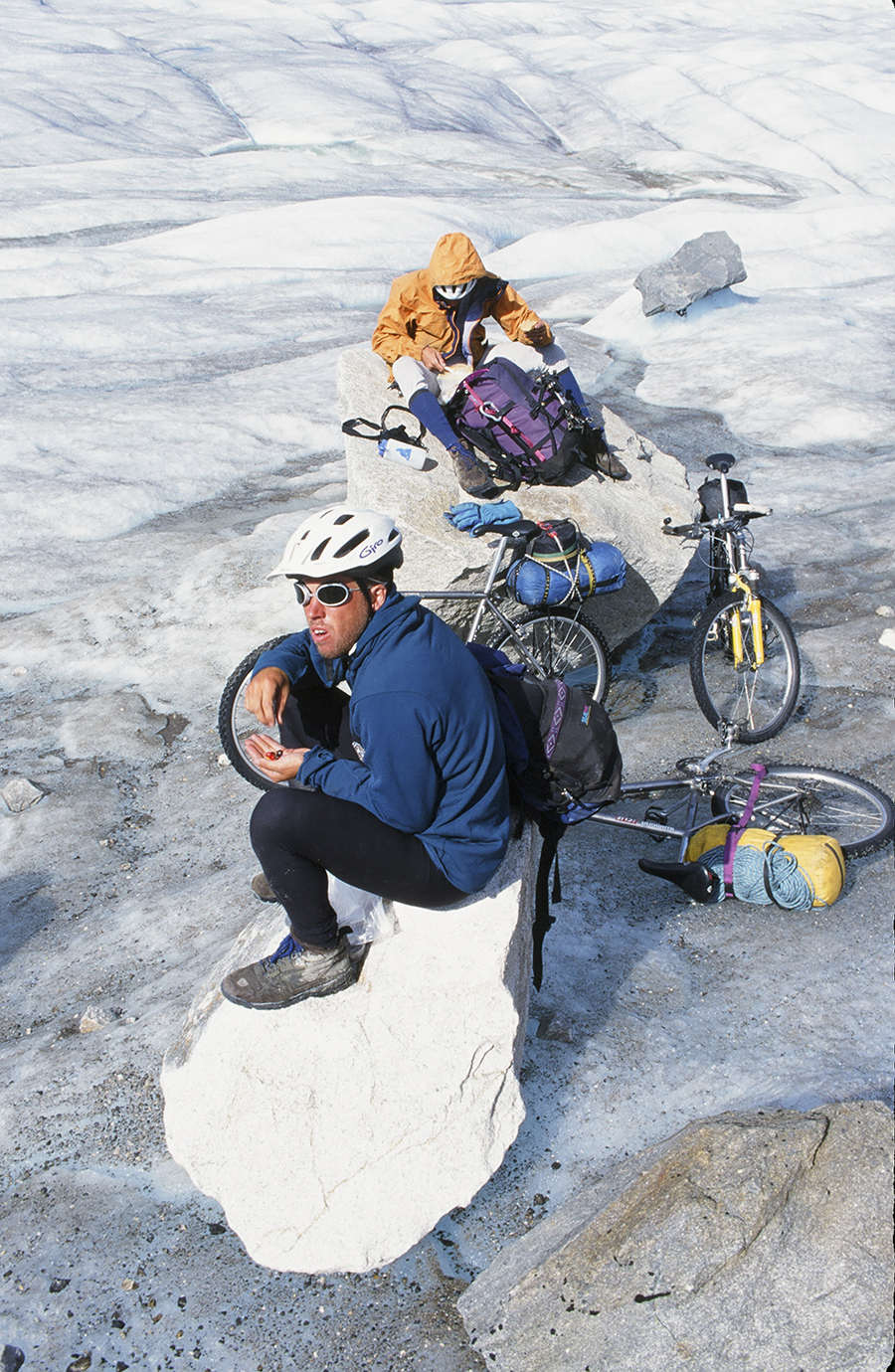

The soggy clouds of August wrapped around black peaks like washrags around bad plumbing, the leaks oozing, dripping, spilling down as big puddles of glacial ice across the valley floor. Jon Underwood, a six-inch crescent wrench in hand, squatted on the aquamarine “sliprock” (hellbiking lingo for a glacier’s naked surface) and eyeballed the situation. At his feet a mountain bike lay crippled, the right pedal snapped off its crank.

“How far to the Denali Highway?” he asked.

Carl Tobin squinted into the distance. “Forty-five, fifty miles. Twenty miles of ice, then thirty miles of river.”

This was a guess. Aside from a shortage of spare pedals, we also lacked a map. Jon set the wrench down, picked up the pedal, turned it in his palm.

“Guess I should have switched both pedals back at Black Rapids.”

Three days earlier, he’d replaced the wobbly feeling left pedal at our resupply point, the Black Rapids Lodge on the Richardson Highway.

“How far back to the lodge?”

Again, we estimated. “Thirty-five, forty miles?”

Thirty-five miles that reached back over a glacier pass, through shin-deep snow, past crevasses, over unstable moraines, through bad brush, and across a river demanding multiple ferries of bikes, men, and gear in our single four-pound, five-foot packraft. This onerous list filled us with a fear of the known. The unknown via the Susitna Glacier didn’t seem so bad. The route was downhill, for example — always a bike tour bonus.

Bike tour? How about mountaineering expedition? Scrambling over the 30-mile Black Rapids Glacier, we had jumped a moulin stream — a vertical shaft in a glacier kept open by pouring water. Then at the pass, portaging bikes like pillories, we had roped up and trudged five miles through a crevassed snowfield, always wondering, “Clip-in to the bike? Unclip from the bike? Which way to best survive a crevasse fall?” Which way to rationalize an absurdity?

Over the years, we’ve developed a taxonomy for crevasses. Guppies are the smallest. A glacier traveler can bridge these tiny cracks with a size nine boot. Sharks bite extremities, usually a leg (or legs) to the waist. Injury may result but rarely death. Whales can swallow the unfortunate, possibly killing and consuming the body. Rippers are cavernous. A roped climber falling into one of these plunges downward, then pendulums into a distant wall as the rope rips through the ceiling.

How to rationalize an absurdity: walking past whales’ tails and swarms of sharks, loaded bikes cinched tightly around our necks, the snow-slogging portage over the pass had dragged on like a waking nightmare. Yet one day before, on a highway of sunny sliprock stretching from the terminal moraine (the accumulation of stones and debris deposited by the glacier at its toe) to the firn line (where previous years’ snow has been consolidated by thawing and refreezing but not yet been converted to ice), we had rolled — as in a dream — effortless and exhilarated.

Earlier signs had suggested retreat. Jon’s rear rack fell off the first day out of Mentasta at the eastern end of the Alaska Range. Carl inadvertently swam the glacial Chistochina River with his bike on the second day. And on the third day, I realized I’d forgotten the map. By the fifth day, we all saw that we had carried too little food: the leg of our journey that we’d hoped to pedal in six days might take 12. And there, high on the Susitna Glacier, we realized that we had carried too few tools, not enough parts, and no spare pedal.

We discussed abandoning our 250-mile, two-week mountain bike expedition through the glacial gut of the Alaska Range following the Denali Fault. Why had we pushed on this far anyway? Stubbornness? Stupidity?

Part of the “why” concerned bettering our previous 150-mile hellbike trip through the Wrangell-St. Elias from Nabesna to McCarthy. Some of it had to do with my own plans for an even bigger, full-length traverse of the Alaska Range. I would start with these 250 miles of mountain biking through the Hayes Range, then follow that with 450 miles of walking across the Denali and Lake Clark National Parks. For Jon the trip simply answered the query, “What’s next?” after Nabesna to McCarthy. As for Carl, a 2,000-foot avalanche ride down a north face had permanently subtracted nearly 90 degrees of motion from his knee. The accident had occurred in this very mountain range at the height of his climbing career. Hellbiking offered him a new medium to paint bold, defiant strokes across wild landscapes, to flip the finger at conventional wisdom’s button-down view of the possible.

Conventional wisdom viewed mountain bikes as alien to the Alaska Range, a view concerned less about the impact of rubber knobs on the environment than with the damned hard impact of the environment on riders, their bicycles, and, alas, their pedals. Conventionally wise people claimed bikes can’t be ridden on glacier ice, crevasses are treacherous, and big wilderness is too big for bikes. These people said, “Bicycles should stay on the road.”

We responded that creativity is the bastard child of the conventional: the art of adventure is what we do, and the science of adventure is what we prove.

Back at the broken pedal, I posed a hypothesis. “How ’bout Jon takes the raft and the paddle and goes out the Susitna alone, and we take the rest and head over to the Gillam?” The Gillam was the next glacier leg on our tour, several miles away over a 7,000-foot pass.

Jon, here on his first-ever glacier trip and second-ever wilderness trip, looking at 50 miles of raw wilderness over glaciers, rivers, and brush, with no map, no partner, and no right pedal, answered simply, “What’s the river like?”

“As I recall, it’s big, slow, and full of quicksand,” volunteered Carl, who’d floated it twice after climbing Mounts Deborah, Hess, and Hayes.

A swarm of crevasses, like sharks schooling from the depths, creased the snow up-glacier.

“Let’s get down to the moraine and talk about this,” I suggested.

In blowing rain, we mounted our bikes and began coasting down the glacier.

Sunny sliprock bears the same resemblance to icy winter roads of civilization that granite cliffs bear to concrete slabs: superficially similar but aesthetically distinct. Peppered in pebbles or dusted in loess, the ice often lays naked, its blue-, green-, or white-hued flesh pockmarked and rough-skinned. Sunshine revealed compressed ice as a wonderland of traction, an alpine version of Moab’s celebrated sandstone, with rolling basins, steep headwalls, and tight, narrow ridges. Like its Utah namesake, sliprock as a medium inspires the rider. The surface, anchored beneath spectacular mountain scenery, creates an extraordinary experience as cycling adventure.

Extraordinarily miserable, that is, in the rain, going downhill in gusty high winds, bikes laden with Patagonia pile, ice ax, packraft, and more food than we wanted to carry but less than we needed to eat. As usual, we had eschewed panniers, instead strapping loads onto a rear rack and half-filling our rucksacks with gear. This way we could shift the load depending on the balance of riding versus carrying in a fixed position no matter what each day offered. Unfortunately, as the corrugated ice dropped at 300 feet per mile, any load at all — backpack or bikepack — was unwelcome.

Soon we’d each spilled and bumped our butts sufficiently hard that slipping on foot instead of on studless tires seemed safer. Five tight-jawed miles later, chanting Talking Heads’ “Psycho Killer” (“I’m tense and nervous / And I can’t relax”), we embraced the medial moraine as an old friend — a friend we’d normally avoid.

Cold, wet, and miserable, we pitched camp in the lee of a Subaru-sized boulder, paving the floor and lower walls of our floorless, nylon pyramid tent — held up by our packraft paddle — with flagstones. Inside the airy blue tent, warmed by the cookstove’s heat, we kept the outer bleakness at bay and talked cold turkey.

Carl is a Himalayan veteran with radical first ascents in Alaska and Canada. Recently, he’d been kicking ass as a mountain bike racer. Together we’d shared a rope on rock, ice, and snow for more than a decade. Indeed, I had apprenticed much of my mountain wilderness experience under his tutelage. Consequently, when Carl spoke, Jon and I listened to our elder.

“I predict, if tomorrow’s like today, we’re not going up to Icy Pass and over to the Gillam. We’re all going down with you, Jon, out to the Denali Highway.”

I’d risked my life with, and even for, Carl. This provided me some veto power in response to proclamations like, We’re all going down and other statements of retreat.

My dreams of a full-range traverse were at risk here. Hundreds of miles of Alaska’s wildest terrain to fumble and fondle were slipping from my grasp. I wasn’t ready for this expedition to dissolve just yet.

“Hold on a minute,” I stammered. “Why not wait out the weather, like we would on an alpine climb? We know the ice is out of condition now, but with some sunshine — ”

“It’ll shape up into something rideable?” Jon laughed and clapped his hands together.

“Like on the Black Rapids? Best riding of the trip. But we only have one day. We don’t have enough food to wait out longer.”

The next day, the peaks were engulfed in storm. Jon puttered about the tent. I greased my hubs, bottom bracket, and headset. Carl took a break from the ’mid and searched for food that he and a climbing partner, David Cheesmond, had stashed after the first ascent of Mount Deborah’s east ridge six years earlier. Finding that food cache would’ve encouraged us with needed rations and a good omen.

But instead of clearing, the clouds slipped off the mountains and slid down to envelop us, aborting Carl’s search and soaking our already soggy spirits. We could stretch our food four more days, enough to finish the remaining 100 miles of our planned route, but only if the weather cleared.

The second night passed at our boulder-strewn camp, but the weather remained. Drizzle dripped from peak-clogging fog. We all knew what this meant: a Susitna bailout.

Nobody spoke. Victims of the conventional, we loaded gear into stuff sacks and backpacks and prepared for retreat.

“So, bikes don’t belong in the gut of the Alaska Range after all,” I mused to myself, disappointed that my Alaska Range traverse would have a hundred-mile gap in it.

Stuffing the ’mid, my disappointment erupted like a festering boil.

“Listen: I’m taking the rope, the axe, crampons, megamid, and stove and going over the pass anyway!” I said.

Carl answered in a heartbeat, “Not without me, you’re not.”

Jon’s face twisted wryly into a grin. “Guess that means I’m going, too.”

Unanimously, we asserted ourselves, full of empowered self-determination to prove again that in the science of adventure, egos outsize brains. We headed off up-glacier.

While the west-facing Susitna had offered all the traction of an inclined hockey rink, the south-facing glacier leading to Icy Pass surprised us with its traction. Equally remarkable, Carl discovered the Tobin-Cheesmond cache of peanuts and kippers. God does indeed smile on us mortals of simple mind.

Encouraged, we pedaled higher. Bare ice and rain gave way to névé and sleet, the wind increasing with altitude. At 7,000 feet, we dropped our bikes, punched into a whiteout, and followed our compass north to the col, scouting the route over the divide.

This was full-on stupid. I wore every stitch of clothing I’d brought, from pile pajamas to Capilene balaclava, all worn as armor against the cross fire in a battle of the air masses. There along the crest of the Alaska Range, a coastal low-pressure system struggled with an interior high for supremacy. Caught between combatants, we stumbled upward, three fools linked by 120 feet of five-millimeter Kevlar cord and the same mentality that sends dogs after porcupines again and again.

We reached the col, anchored our packs in the lee, then returned for our bikes. The wind twisted and jerked the bicycles on our backs as we stepped over the divide. An icy ramp led left, merging with a glacial bulge split by crevasses. We crept along, winding our way through a historical impasse recorded in David Roberts’s 1970 expedition classic, Deborah: A Wilderness Narrative.

Nearly 30 years earlier, a whale had swallowed Don Jensen, roped to Roberts for safety, then chewed him up and spit him out at Roberts’s urging. Two decades later, these crevasses again enforced retreat when a pair of experienced Fairbanks ski mountaineers balked at the maze.

Icy Pass had turned back both groups. We felt honored: the col let the bicycles pass.

Safe on the snow flats below, we looked back. The science of adventure had proven itself irrational: during a blizzard, 60 miles from any road or man-made trail, over a pass that repulsed experienced mountaineers, we’d crossed the glacial spine of the Alaska Range with mountain bikes. The idea of it made me sick.

We pedaled down-glacier, bunny-hopped a few guppies, but mostly bike-hiked through ankle-deep slush. Near midnight, we anchored the ’mid to a rocky moraine. The shelter barely survived a thrashing storm. With great relief, we exited the glacial system the next day. As Jon’s first experience with glaciers had stretched rather uncomfortably over a hundred miles and a week, he swore them off, if not forever, at least for a day.

Two days later, we nearly lost ourselves again high on ice in swirling clouds. Like the proverbial three blind men feeling an elephant, each of us massaged his memory of the map, and each arrived at different conclusions. Until this point, we’d followed glaciers and river valleys familiar from a dozen years of hiking, skiing, climbing, and floating. Now we stumbled around nearly lost on a question mark–shaped glacier, wondering not only where we were but where the hell we should go.

Finally, Carl said, “Let’s go back. We can head for Healy the way I walked out 12 years ago after Clif and I left the Gillam.”

“Can you remember the route, Carl?” I asked.

“Yeah, I think so. We go down the Little Delta, turn left to climb over a tundra plateau, then drop down to a small creek. I think it’s Buchanan Creek. We follow that upstream, climb the pass at its head, and drop down again. That should put us close to the Wood River.”

Down the Little Delta we went, turning left at Carl’s signal, humping our bikes over a tundra plateau, coasting down to the creek bottom below by milking all the elevation we could, gently bumping along the tundra. Then Carl indicated that we climb up to the pass above. We pushed, then portaged to the top, arriving in cloud. So far, so good.

Carl waited as peaks tore a hole in the weather. He took in what the view revealed, turned around, looked from whence we’d come, and looked ahead again. With a perfectly straight face, he announced, “Nope, this isn’t it. I’ve never been here before in my life.”

This was funny, hilarious even — an excellent joke.

“No really, Clif and I must have gone farther north before climbing up. It was 12 years ago.”

Off memory’s map, we pulled out the compass and aimed it over the pass: west. Thank God. Salvation. At least we weren’t lost. Sure, we didn’t know where we were, but that’s only half of being lost. The other half is not knowing where to proceed.

We knew where to proceed. We climbed into our saddles, pushed off, and pedaled into the fog, heading west.

Okay, so usually we carry maps. And we think about the maps we carry. We prefer the 1:250,000 scale USGS Alaska topos. These sheets show the big picture, the prominent landmarks needed in regions where no marked routes exist at all. Useful landmarks show up more clearly on the four-miles-to-the-inch quads than they do on the one-mile-to-the-inch maps, where the important contours sometimes get diluted in detail. Beside that, a 200-mile trip fits conveniently on two big maps, a lighter and more manageable load than 15 or 20 of the 1:63,360 scale.

The cabins shown on Alaskan topos, most mapped before I was born, usually no longer exist. Rarely does anyone own or permanently occupy those that do. Hunters and trappers maintain them for temporary use.

I confess that we sometimes find shelter in these crude cabins. We look for cabins on the map, and if we are near, we visit, sometimes meeting extraordinary people. But wandering around half-lost on the north side of the Alaska Range, my mind grappled with the irony of looking for a cabin to find a map.

Of course, we did find a cabin with a map inside it and then located the cabin on the map in a weird sort of wilderness recursion. We were right where we wanted to be. Carl couldn’t have done better if his memory had been cartographic.

We even found a lodge where the master hunting guide within, Lynn Castle, insisted we lay down our bikes and explain how in the hell we’d made it 200 miles through the Alaskan bush on bicycles. “Those things got motors?” he asked. Then we feasted with him, bathed in a sauna, slept in beds, feasted again, and in the morning rode on.

Lynn promised the final 30 miles would pass in six hours. It took 12, much of it in a dry creek bed with pool drop architecture. The creek bed exhilarated me but depressed poor, pedal-stub Jon. Until then, where stand-up balance was crucial, Jon had kept up admirably, toeing the pedal’s inch-long axle stub the 100 miles since breaking it. The inconvenience — compounded by a blown transmission in the Wood River valley when a stick in the spokes snapped a derailer — slowed Jon little on our route of gravel river bars, wild animal trails, and firm downhill tundra. But the look on his face said it was getting old, and the hole wearing at the toe of his shoe said likewise.

We arrived in Healy at a Parks Highway roadhouse, just north of Denali National Park, late in the evening of our 14th day. Stinky, beat, and happy, we gulped two full meals apiece in an hour.

Sitting there with a belly full of greasy goodness, I appraised the value of persistence. We’d endured daily rain, skimpy rations, broken bikes, self-doubts. We’d crossed big rivers, bigger glaciers, the biggest mountain range in Alaska. Our mechanisms for success? Jon’s enthusiasm and Carl’s wisdom keeping us rolling confidently on wheels well lubed with humor.

By trip’s end, we claimed again: “Our mission? To boldly bike where none have biked before!”

Or, likely, would ever again.

A professor of mathematics and biology at Alaska Pacific University in Anchorage, Dial has written two books: Packrafting! An Introduction and How-to Guide (Beartooth Mountain Press, 2007) and The Adventurer’s Son (William Morrow, 2020).

This story originally appeared in Wheels on Ice: Stories of Cycling in Alaska (edited by Jessica Cherry and Frank Soos; University of Nebraska Press, 2022). Reprinted with permission.