Eastman & Overman

This article first appeared in the June 2016 issue of Adventure Cyclist magazine.

George Eastman, the founder of Eastman Kodak Company, was one of America’s greatest (and richest) innovators of the 20th century, on a par with Thomas Edison and Henry Ford (whom he counted as friends). Like another acquaintance, John D. Rockefeller, Eastman would give away tens of millions of dollars before his declining health compelled him to take his own life in 1932. Today his name lives on thanks to the many institutions he supported, not to mention the George Eastman Museum in Rochester, New York, dedicated to sustaining Eastman’s legacy.

Not so well known — forgotten, in fact — is the name of Eastman’s close friend and confidante for many years, the bicycle magnate Albert H. Overman. No memorial recalls his name. Not in Normal, Illinois, his birthplace, nor in Chicopee Falls, Massachusetts, where his sprawling factories once hummed day and night. Not even in Westmoreland, New Hampshire, where in 1930 his ashes were strewn over his beloved Bonnie Brook farm.

And yet when these two industrialists met aboard the steamer City of New York in the fall of 1894, it was Overman who was the bigger cog. To be sure, the 40-year-old Eastman, after years of struggle, was starting to make a name for himself with his new line of Kodak film cameras, which would revolutionize photography and lay the foundation for his vast fortune. But it was Overman, Eastman’s senior by four years, who presided over the booming bicycle industry; his company was already one of the largest in the country and growing.

And it was Eastman, the cycling fanatic, who respectfully reached out to Overman after learning that the prestigious bicycle maker was aboard the same ship. Fearful of a personal rebuff, the shy Eastman sent an emissary to do his bidding. Years later, Overman recalled the incident in a letter to Eastman. “Some man on the boat came to me and said that Mr. Eastman would like to be introduced to me. I said ‘Very well.’ Thereupon he took me and introduced me to you … This is as fresh in my mind as a photograph.”

What ensued was an extraordinary friendship, built on frequent correspondence, numerous encounters, and joint business and pleasure trips. They constantly exchanged photographs and goods, sought each other’s counsel, and even co-purchased and shared a hunting lodge.

What drew them together, and why did they fall apart? The answers have remained largely hidden in the mountain of personal correspondence conserved at the Eastman Museum. With the invaluable help of the resident archivist Jesse Peers, an avid cyclist, I pieced together the following account.

The catalyst for the friendship was clearly Eastman’s passion for cycling. He was no Johnny-come-lately to the sport either, having lived through Rochester’s “velocipede mania” of 1869. Although he was only a lad of 15 at the time, he had already been working as an errand boy to help support his mother and two sisters, his father having passed away some years before. His meticulous expense ledger shows that he spent a total of $20 that year on exercise classes at a gymnasium, which might well have included a few jaunts on the primitive boneshaker.

In any event, he was among Rochester’s pioneer riders of the high wheeler. In 1879, when he made his first journey to London to patent his dry plate coating machine, he probably noticed how popular the sport had become there. The following year, the Rochester Bicycle Club was formed. As a young, unmarried bank clerk with a good salary, he was prime recruitment material. In 1881, he wrote to Singer & Co. in London to order a 50-inch Challenge, which he would ride regularly from his home to his office.

In the summer of 1892, during another visit to London to tend to Kodak’s growing European business, Eastman transitioned to the up-and-coming pneumatic “safety” bicycle. He and two business associates rented three bicycles, and for three weeks they cycled around southern England, visiting historic hamlets such as Windsor and Canterbury. Eastman found the experience so exhilarating that he simply “forgot business.”

The following year dealt Eastman a nearly disastrous one-two punch: an acute national depression and a mutiny at the Kodak plant. He was forced to curtail his leisure cycling to concentrate on keeping his business afloat. But by mid-1894, with the Kodak ship righted, he was ready to re-immerse himself in the sport. He was impressed by the rapid development of the safety bicycle, remarking about a friend’s 17-pound model: “You can take it up in one hand and swing it over your head. Such a reduction in weight must add to the pleasure of touring.”

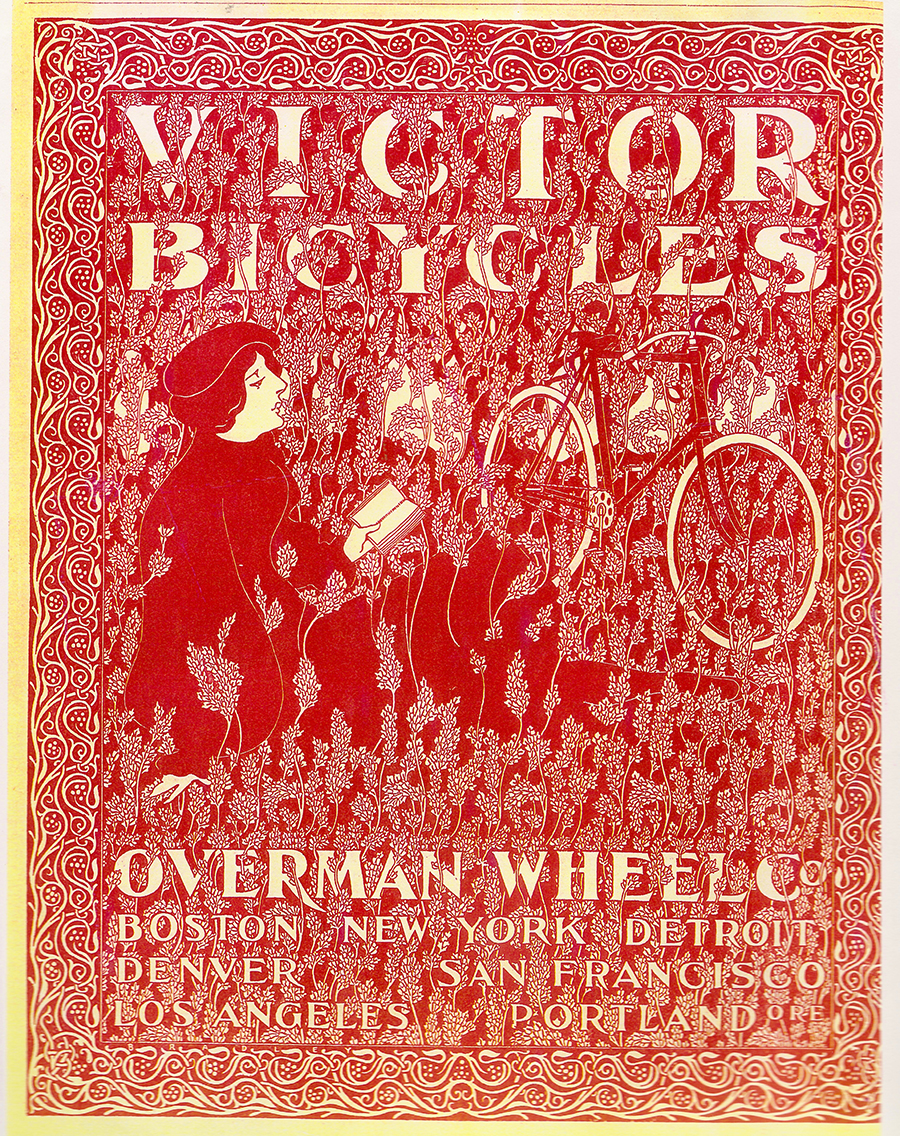

Eastman and Overman bonded immediately. The bicycle man also came from humble roots and had built up a bustling business from scratch. In 1882, he settled in Springfield, Massachusetts, and set up a factory in nearby Chicopee Falls to make high-end tricycles under the brand Victor. After the expiration of the Lallement patent the following year, Overman made high wheel bicycles. In 1887, he introduced the first American-made safety, sparking the great boom.

One might suppose that Overman took a similar interest in Eastman’s wares. After all, both products were undergoing similar popular transformations and they went well together, as the recent “round-the-world” journey of Allen and Sachtleben underscored (they took hundreds of negatives with their Kodak #2, some of which still survive and have been printed in the June 2013, 2014 and 2015 issues of Adventure Cyclist).

But Overman was no camera buff. On the contrary, he confided to Eastman early on that he had long supposed that photography “would be one of the crazes which would not attack me.” That indifference would soon give way to passion.

In July 1895, Eastman sent Overman a Pocket Kodak. Overman was “pleasantly surprised” by the unsolicited gift and immediately “studied it up.” He was especially impressed with its practical design, which showed “a lot of thinking out of the little details.” Before long, Overman admitted to Eastman, “I am getting to be one of those ‘Kodak fiends’ you hear of so often.”

Overman, in turn, offered to send Eastman one of his own creations. That’s when Eastman had to come clean: he rode a Columbia, made by Overman’s archrival, the Pope Manufacturing Company. He broke the news gently. “The Victor is decidedly the queen of wheels in this city, but I bought a Columbia because the Victor was ‘out of sight,’ that is, all that were in sight had been spoken for.”

Overman, who dreaded the idea of Eastman “knocking about on an old Columbia,” wasn’t buying Eastman’s excuse. The Victor man probably intuited, correctly, that when the frugal Eastman wrote “out of sight,” he was really referring to the Victor’s inflated price tag. After all, Overman’s own ads boasted that it was the most expensively made bicycle, every part being manufactured on site.

“I’m very sorry the Victor was ‘out of sight,’” Overman replied, quoting back Eastman’s words. “If you will just tell me what size and equipment you want, I shall be very pleased to send one to you.”

Eastman at first clung to his story, lamenting: “I am sorry I could not get a Victor. I should have taken a great deal more pleasure in riding a machine whose maker I knew.” But, after further prodding from Overman, he finally relented. “It seems almost a sin for you to send me a bicycle when I have a bran [sic] new one. However, I shall be delighted to ride a Victor if you want me to. I am 5’ 7” high and weigh about 135 pounds.” He had only one request: that it come without brakes, which he deemed “very dangerous things.”

Eastman promptly took his new Victor to Europe, touring France with three business associates. He was elated with his new wheel and let Overman know it. “Am glad the wheel has served you well,” Overman replied triumphantly. “I expected it to do so.”

Overman, for his part, continued to make good use of his Pocket Kodak. “I have just returned from a moose hunt in Nova Scotia,” he wrote Eastman in October, “and it was a constant delight to me.” Eastman replied: “Am glad that you are partially converted to the faith. To complete the job, I am sending you a #5 Folding Kodak.” A few days later, Overman responded, “I can hardly tell you how pleased I am with this set of tricks. I am like a boy with a new toy. I hope to take some pictures which even you will not be ashamed of.”

Still feeling indebted to Overman, Eastman ordered three Victors to be sent to his cycling mates in London. “I shall give you the ’96 models,” Overman promised, “and a special price on them.” Asked about including a rumored “changeable gear” mechanism (the standard bicycle at the time had a single fixed gear) Overman balked, “Changeable gears are a delusion. They will always be complicated and of very little use.”

In February 1896, the three Victors arrived in England. One of the recipients, Joseph Thacher Clarke, was particularly grateful for his “magnificent machine.” He got an extra-sturdy model to accommodate his six-foot frame and 200 pounds, which he found “more rigid than my large and heavy Whitworth cycle,” the machine Eastman had dubbed a “man-killer.”

With summer approaching, Eastman again made plans for a bicycle trip in Europe. He invited Overman to join him, but the Victor man offered a counterproposal: a three-week train tour of Eastern Europe, to include a visit to Moscow. The idea intrigued Eastman, but he was reluctant to give up any cycling time. Overman prodded his friend once again, “It is well worth while to have a look at [Russia], and very much pleasanter if two can go together into a strange land. We might be able to make some kind of joint deal there.”

Eastman at last accepted, and the two converged in Paris. There they rode the Orient Express for 25 hours, alighting in Vienna, where they toured art galleries. Continuing to Warsaw, Eastman struggled to explain to Polish officials the purpose of the half-dozen boxes of film in his trunk. Overman, meanwhile, had to clear the bicycle he intended to show potential business partners. Perplexed by the agents’ animated reaction, Overman emptied his pockets of cash before he finally understood that the bicycle would be admitted duty-free.

In Moscow officials stopped Eastman from taking photographs, informing him that he would need a permit. “This is the most foreign place I have ever been to,” Eastman wrote his mother. “Not a word anywhere that one can read. Strange faces, costumes, vehicles, and buildings.”

The pair traveled 250 miles east of Moscow to Nizhny to attend a trade fair. Hearing that the czar would be parading through town, they chose a hotel along the route. The next morning, while breakfasting on the veranda, they looked down at the royal entourage. “The Emperor looked up and saw me with my camera and acknowledged my salute,” Eastman wrote his mother, though he lamented, “the carriages were going so fast I probably didn’t get anything of a picture.”

The two continued on to Stockholm and Copenhagen before parting ways. “I have enjoyed the trip greatly,” Eastman told his mother, “but am tired of going from big town to big town and shall be glad to get out into the country on my wheel.” Eastman managed to do just that after a brief stint in Paris attending to business. This time he and Clarke went on a tour of Spain. “We had a very good time on the wheel, even better than last year,” Eastman wrote his mother. Clarke concurred, writing Eastman, “I should be delighted to make another [cycling trip] with you, at any time, and to any place.”

Though Overman and Eastman were now physically apart, their bond gradually tightened. Sailing back to New York that October, at Overman’s request, Eastman accompanied Mrs. Overman. Upon his return, Eastman bought $5,000 of stock in the Overman Wheel Company and sent Overman the blueprints of his factory under construction at Kodak Park to encourage Overman to expand his own plant.

Overman, for his part, pressured Eastman to join him in North Carolina to shoot quail. “If I find when I get my gun that I can hit anything with it,” Eastman promised, “I shall accept.” Eastman soon agreed to Overman’s proposition to co-purchase a 7,500-acre plot in Halifax County, North Carolina, where they would build a cottage to be known as Oak Lodge. In July, Eastman joined the Overmans at their New Hampshire farm called Bonnie Brook, some 70 miles up the Connecticut River from the Victor plant. There he received hunting lessons from Overman in exchange for preparing the family meals. “When I master every method of cooking eggs,” Eastman cracked, “I am going to tackle another branch of cooking.”

A dramatic development at the end of that year, however, signaled not only the imminent demise of the American bicycle industry but also trouble ahead for the Overman/Eastman friendship. The Friday before Christmas, when some 1,000 Overman Wheel Company employees came to collect their weekly paychecks, they were shocked to learn that their services were no longer needed. The great Victor company was bankrupt, and it would never recover.

Overman, who owned two-thirds of the company’s stock, blamed the company’s downfall on a bad economy that had led to an overproduction of shoddy bicycles, though others suggested that he had overextended himself by dabbling in the production of non-cycling sporting goods.

Whatever the cause, the New York World published an unflattering portrait of the man behind the debacle. “Overman lived magnificently and entertained lavishly,” read the subtitle. It cited how he had built a “costly” home in Springfield on the corner of Pearl and Federal with an array of stables behind it, hired a personal chef to prepare exquisite meals at the factory, and wasted money underwriting a seldom-used athletic park near the factory and a company band.

In mid-1898, Eastman received a letter from the creditors of the Overman Wheel Company with a check representing a return of only 25 percent of his original $5,000 investment. Overman, however, promised to make up the difference, and the friendship appeared to have survived unscathed. The two continued to exchange cordial letters, mostly about the management of Oak Lodge, and occasionally to telephone or see each other. And Overman continued to shower Eastman with gifts, including bags of coffee beans and jars of homemade maple syrup.

An incident in May 1899, however, underscored just how far Overman had fallen from the class of “fat cats.” When Overman wrote to Eastman to request the return of an umbrella that he had accidentally left behind during a recent visit, Eastman naturally assumed that it was a precious object befitting a fellow captain of industry. After rummaging through his collection of abandoned umbrellas, Eastman asked innocently, “Is it the gold-headed one, with a diamond and rubies in the handle or the one with pearls all around the edge?” “Nay, nay, Pauline!” replied Overman, borrowing the title of a popular song. “Neither rubies nor pearls. Not even gold. Just a plain, ordinary, handle.”

Overman would try mightily to get back on his feet. In mid-1899, he produced a steam-powered automobile, and he announced his intention to manufacture the Victor Steam Carriage through the Overman Automobile Company in Chicopee Falls as soon as he could find sufficient backing from investors.

Eastman, who was now more interested in motoring than bicycling, was carefully studying the emerging and highly competitive automobile industry, trying to gauge which of the three prevalent powering technologies — electric, gasoline, or steam — would ultimately win out. He was not keen on gasoline-powered vehicles, which he deemed fit only for “racers.” He was partial to the electric car, admitting to Overman that he had ridden a Columbia “and they nearly got my order.” But he insisted that he, too, was a “steam man” at heart.

Eastman test rode Overman’s prototype, and while he offered no investment money he did pledge to buy a Victor automobile “when you have got it in thoroughly good, reliable shape.” He confided to Henry Strong, Kodak’s president, “[Overman] ought to make a lot of money … but his financial difficulties may hamper him.”

In the meantime, Eastman began to look at two steam-powered automobiles already on the market: the Stanley and the Locomobile. In November of 1899, he asked a friend to buy the latter on his behalf, explaining, “I do not wish to order this machine in my own name on account of my friendly relations with Mr. Overman.”

In November 1900, the Victor was still not on the market, but Eastman examined an improved prototype. “I was delighted with it,” Eastman wrote Overman, although he also suggested numerous possible improvements. “If you can get your machine on the market this coming spring,” Eastman advised, “you will be overwhelmed by orders. Every minute delay, however, will give [competitors] an opportunity to crawl up on you.”

Finally, in May 1901, assured that production of the Victor was underway, Eastman put in his order, sending Overman a check for $1,000. But, when the Victor finally arrived three months later, Eastman could not get it “in running order.” Knowing that Overman was back in Europe, Eastman complained directly to the company. They promptly sent a mechanic to Rochester to start the machine but success was short-lived. “I took the Victor Automobile out twice immediately after your expert had been here,” Eastman wrote back to the company, “and the second trip burned the boiler. I am returning [the vehicle] to your factory.”

Then Eastman wrote a long letter to Overman ticking off a host of technical problems with his Victor as well as possible solutions. “I am sure you will take this letter in the spirit it is written,” Eastman affirmed. “I am truly interested in your success and it is my duty as a friend to tell you that I think you are on the wrong road.”

The company responded first: “We are sorry to hear that you have had so much trouble with your carriage. We now have some 15 or 16 carriages out and, with but few exceptions, we are having no complaints. As your carriage was one of the first assembled, it was not as carefully put together as the subsequent ones. We want to make this carriage entirely satisfactory to you.”

Then came a six-page handwritten letter from Overman himself, who was finally back in Massachusetts. “Your letter [brought] grief to me. I was so anxious to finally win your approval of my machine,” Overman opened. “In no case has the result of a sale been so disastrous as in yours and I am primarily to blame,” he conceded. “When the machine was sent you, the company was changing superintendents and I was in Europe. It should not have been sent in the condition it was.”

But then Overman voiced a gripe of his own, alleging that John Brisben Walker, the owner of Cosmopolitan magazine, was all set to back Overman’s European venture until he heard Eastman lament, “Poor Overman! Everything he has tried to do has been done before.”

“The task of building up a new business on the wreck of an old one is heavy,” Overman continued, “but it must be done. I believe in my undertaking and will make every sacrifice to win out with it. My home is offered for sale and I feel that I ought to dispose of my part of Oak Lodge also.”

Eastman agreed to buy Overman’s share of Oak Lodge, subtracting the balance due from the Overman Wheel Company. He insisted that Overman would always be welcome there, but the friendship was effectively over. For his part, Overman kept Eastman’s car and promised to sell it for him — but never did.

It would appear that it was primarily Eastman who lost faith and interest in the friendship, but why? The simplest explanation would be that as Eastman’s passion for the bicycle faded, so did his interest in Overman. But that is unlikely to have been the primary reason as they shared so many other interests.

Financial tensions, stemming from the bankruptcy of the Overman Wheel Company, clearly took a toll on the friendship, even though Overman took pains to square matters with Eastman. And the Victor “lemon” certainly exacerbated tensions. Still, it seems that their long friendship should have been strong enough to survive these rifts.

The inescapable conclusion is that Eastman’s opinion of Overman diminished over time. The negative press about Overman, depicting him as a bon vivant who lived beyond his means and grossly mismanaged other people’s money, may have been a contributing factor. But chances are that Eastman himself reached similar conclusions based on his own interactions with Overman.

Overman himself seems to have concluded as much. In 1922, by then retired to Bonnie Brook, he reached out to his old friend, breaking some 15 years of silence. Reacting to Eastman’s well-publicized gift creating a music school in Rochester, Overman wrote:

Say son — what a nice long rest I have given you! But I can’t be still always. With your singing songs for the betterment of humanity, I simply must shout, & do it big so that G.E. will hear it & know that I am looking on & giving thanks that I am alive to see it. Go it Boy! You are your own best pilot, & I hope that no effort of yours will fall into the hands of unworthy loafers who simply look for something to lean against. I am here in the woods hard at work making the most of things & I like it. Life to me is one grand symphony. I am still the man who wants nothing. My kind regards, A. H. Overman

Reading between the lines, one is tempted to deduce that Overman wanted Eastman to know that he, Overman, was never an “unworthy loafer” who tried to take advantage of Eastman’s wealth and influence. And that even though he, Overman, had suffered severe setbacks in business, he was content that he could still afford the essentials in life.

Eastman’s response was polite but terse and aloof. “I was glad to receive your cheerful note and to know that things are well with you and that you are happy. That is the most anyone can get out of life no matter what they do.”

Four years later, in 1926, Overman made another futile attempt to reconnect with his old friend. This time, he reacted to newspaper reports that the elderly Eastman, practicing the sport Overman had introduced him to, had successfully slain an elephant in Africa. “I want to congratulate you on your safe return from your great hunt,” Overman offered. “I have enjoyed immensely your photos in the Sunday Times.”

Another four years later, in August 1930, Eastman wrote his last letter to Overman — this time to Max, the elder son, not Albert. “I am truly sorry to hear about the death of your father. Although I have not had the privilege of seeing him for some years, my remembrance of our acquaintance is very pleasant.”

“Acquaintance” hardly seems a worthy description of the tight bond that once connected Eastman and Overman. In the final analysis, its undoing may be due to the simple fact that the business careers of Eastman and Overman followed opposite trajectories — and the resulting tensions simply proved too much for the friendship to bear.