A Winter Pause in Athens

This article first appeared in the June 2013 issue of Adventure Cyclist magazine.

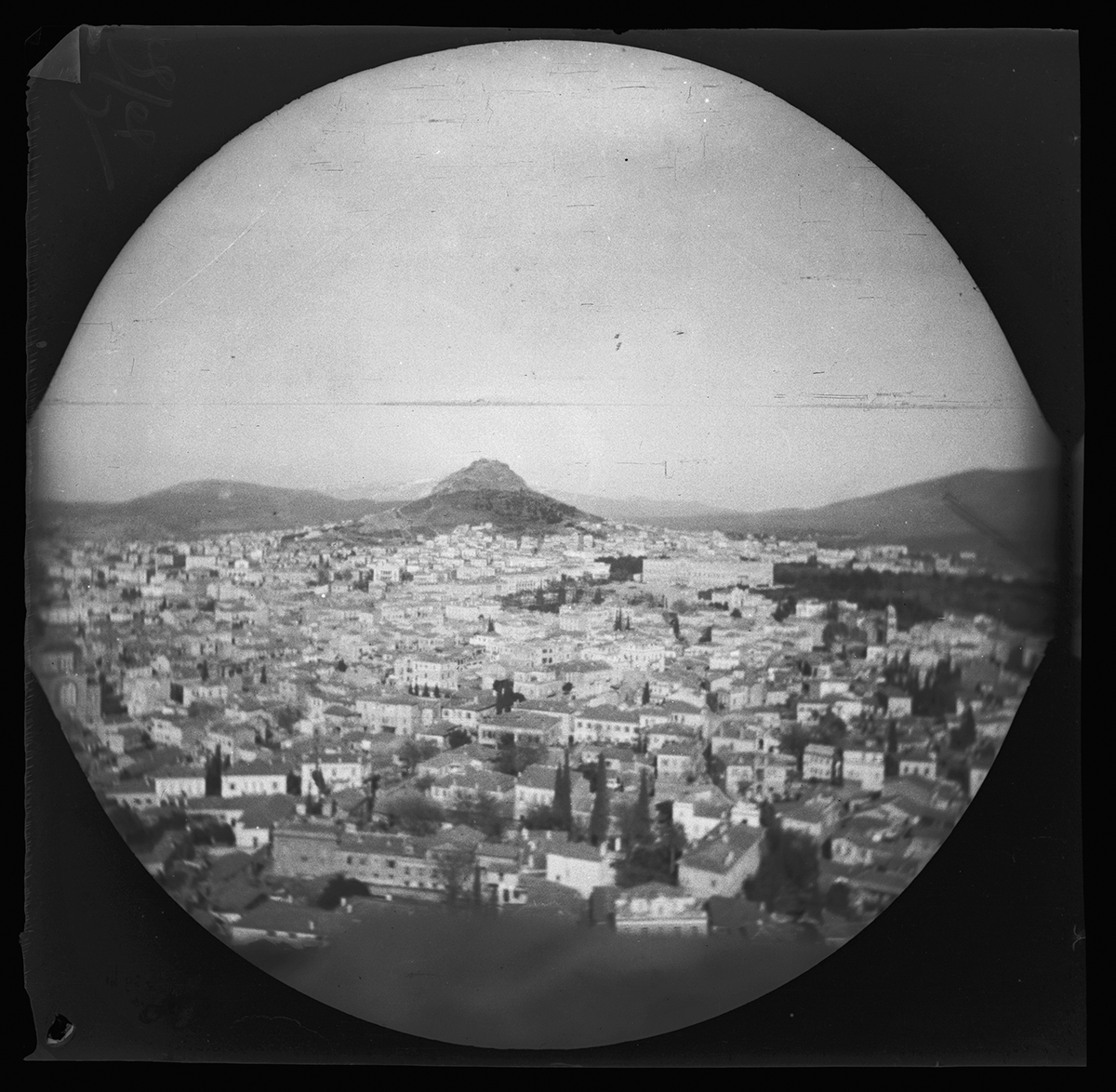

For the past 30 years, Special Collections at the University of California at Los Angeles has held some 400 fragile nitrate negatives taken well over a century ago by the celebrated cyclists Willam Sachtleben and Thomas Allen with an early Kodak camera. At last, the majority of them have been scanned. David Herlihy, who traced their round-the-world journey, as well as that of Frank Lenz, in his book The Lost Cyclist recounts their adventures in Greece, where they spent the winter of 1890-91, before heading across Asia. These photos had never been published before this article.

As the year 1891 dawned, William L. Sachtleben and Thomas G. Allen Jr. reached Athens, Greece, poised to wait out the winter while preparing for an historic 7,000-mile bicycle ride across Asia.

Some six months earlier, the pair had graduated from Washington University in St. Louis. Rather than settle down to comfortable careers, they decided to see a bit of the world with the help of the latest sensation: the diminutive “safety” (the prototype of the present-day bicycle) that was rapidly eclipsing the high-wheel bicycle or “ordinary” and threatening to open up the elitist world of cycling to men and women of all backgrounds.

Both were fortunate enough to have the means to travel as well as supportive families. Sachtleben was the eldest son of a clothier in Alton, Illinois, a prosperous town 20 miles north of St. Louis along the Mississippi River. Allen, from Kirkland, Missouri, was the son of a county judge.

Sailing to Liverpool, England, immediately after graduation, the two friends each acquired a 40-pound hard-tired Singer bicycle. They proceeded to spend a delightful summer tooling around the British Isles. So enthralled were they by the experience, they decided to continue all the way around the world.

Although they traveled in tandem, there was no mistaking their leader. At 25 years of age, the dark and dashing Sachtleben was a good two years older than his partner. With his fit 150-pound body on a five-foot-seven frame, Sachtleben looked downright Olympian beside Allen, who was an inch shorter and 15 pounds lighter. “So great is the difference between the two,” observed one reporter, “one wonders how Allen could hold his own with his more athletic friend.”

Of course, were they to complete their epic undertaking, they would gain fame, if not fortune. Still the risks were high, especially in Asia, where they would face strange languages, diets, and cultures. They would have to brave the elements and cover vast, empty expanses with little or no recourse to railroads. Most daunting of all, they might face hostile residents who had never before seen a Westerner, let alone their mysterious “flying” machines.

To succeed they would need extensive preparation. After all, only one man, Thomas Stevens, had registered a similar feat a few years earlier, riding an ordinary some 15,000 miles over three continents within three years. And even he had largely failed in his bid to cross Asia.

Reaching London in the fall of 1890, Allen and Sachtleben diligently went about obtaining passports and sponsorships. They ditched their Singers in favor of two lightweight Minnehaha bicycles and acquired two Kodaks, a newly introduced compact film camera. They made arrangements with the Penny Illustrated Paper to send photos and periodic reports for publication in that popular journal.

After announcing their intentions to “girdle the globe” and posing with their bicycles for the Illustrated London News, Allen and Sachtleben sailed to France. In Paris a local bicycle club held a banquet in their honor. In Bordeaux they became good friends with the editor of the cycling review Veloce Sport. In Italy they enjoyed similar hospitality courtesy of the growing cycling community.

But now they were in Athens, living in a cheap hotel and looking ahead to the most difficult part of their journey. Over the winter, they would have much to reassess. For starters, they were down to one working bicycle, which Sachtleben occasionally rode through the city, drawing crowds of onlookers, and in the countryside, where he raced farmers on mule carts. Moreover, their relationship with the Penny Illustrated Paper editor had soured, leaving them with no sponsorship.

Still there would be ample time to sort out all their problems before taking on Asia. For the time being, they resolved to do what most young visitors did in the Greek capital: tour the sights, make friends, and enjoy themselves.

Their first destination, naturally, was the Acropolis. The two cyclists, both steeped in the classics, could only gape at the massive marble remnants. “It is impossible to record my thoughts on first seeing the ruins,” Sachtleben would write that evening in his diary. “I looked upon them with something akin to veneration. Here are the soul-inspiring monuments of the first Republic that breathe freedom.”

After a leisurely stroll about the grounds, the pair picked out a grassy spot by the temple of Athena Nike where they feasted on bread, figs, oranges, cakes, and sweets. They gazed at the metropolis below and the bustling port of Piraeus. In the distance, they could make out the sparkling Saronic Gulf, a cluster of islands, and, on the Peloponnese peninsula, the silhouette of the massif of the Taygetos range.

The two friends quickly adjusted to everyday life in Athens. They found that their smattering of modern Greek, as well as their French, came in handy. Typically, they started their day at a café, sipping thick coffee and devouring heaps of doughnuts drizzled with honey. In between errands to the bank, post office, and grocery store, they visited libraries and museums. In the evenings, they holed up in their quarters with fountain pens to write letters and reports.

Life was nevertheless far from routine. One morning, the Americans were surprised to find everything had shut down, only to learn that it was the Greek Christmas. A week later, on New Year’s Eve, they donned costumes and merrily wheeled their way around the revelers. The next day, they awoke to the sound of cannon volleys. Sachtleben followed a military band to the royal palace just as a bevy of elegant ladies spilled out from a reception. He marveled at their abundant “gold lace, silk, satin, and jewels.”

On another occasion, Sachtleben spotted an ornate carriage just as it was pulling away from the palace gate. He managed to get close enough to it to snap a photograph of the passengers, including the young monarch who waved and smiled at the camera.

Once, as Sachtleben was passing by a café, chairs suddenly began to fly through the air. He watched in horror as two men came to blows. One brandished a knife while the other produced a pistol and began firing from point-blank range. Fortunately, the police soon arrived, taking both combatants into custody.

One day, the young Americans watched the elaborate state funeral of Heinrich Schliemann, the famed German archaeologist who, 20 years earlier, had discovered Homer’s lost city of Troy in modern-day Turkey. “It seemed as if all Athens was out from the number of carriages,” Sachtleben noted. “We followed the procession a piece to the graveyard but turned back before reaching it, the crowd was so thick.”

On the way back, the young men saw a simpler, but no less striking funeral led by chanting priests. “You could see the dead body and face,” Sachtleben recalled. “She was dressed in white garments, and her hair was flying loose in the wind.”

Everyday people often provided curious spectacles. Several times, Sachtleben observed frantic firemen rushing off to duty with pails overflowing with water. He would watch workmen as they methodically restored ruins with ancient tools and milkmen ladling out fresh milk to their customers.

The cyclists enjoyed an active social life of their own. They were regular guests at the luxurious home of A. Loudon Snowden, the American minister to Greece. His son, a budding cyclist, was surprised to learn from the lads one evening that the safety record for the mile stood at 2:30, nearly half a minute faster than the comparable high-wheel record.

The cyclists also became friendly with the American consul, J. Irving Manatt, a former professor of Greek archaeology at the University of Nebraska, who had dragged his wife and five children to Athens in order to be closer to his beloved ruins. Unlike Snowden, the consul was no conversationalist. “As soon as one gets outside the range of his own life, that is, Greece and antiquities, he is not much good,” Sachtleben lamented.

Far more appealing to Sachtleben was Manatt’s pretty teenaged daughter, Winifred. “It is impossible for me to recall the many sweet and foolish things I said in her angelic presence,” Sachtleben recorded one evening. “She, and of course I as well, talked of what a fine time we could have making short excursions on a bicycle. I informed her that I should be delighted to teach her how to ride, and that seemed to tickle her very much. She then hinted how fine it was to be on the Acropolis in the moonlight and how sentimental such a walk would be one fine evening.”

One of the most colorful characters the cyclists met in Athens was Seropé A. Gürdjian, an Armenian American and a Bowdoin College graduate. Cerebral and charismatic, he spoke fluent English, Turkish, and Persian. He, in turn, admired the Americans’ pluck and fancy hardware, especially their Kodaks and bicycles. The three began to spend hours together, at cafés in the daytime and in their respective hotel rooms in the evening.

Gürdjian explained that he had recently moved from Constantinople to Athens, after Ottoman authorities had marked him as an Armenian revolutionary. Indeed, Gürdjian made no effort to conceal his disdain for the sultan Abdul Hamid II, the despot who ruled the decaying Ottoman Empire with an iron fist. “I wish his damned carcass would rot in a place worse than hell,” he told the cyclists.

Gürdjian, who had endured torture and imprisonment at the hands of Turkish authorities, was prone to launch into hateful tirades, which only heightened his friends’ desire to visit the so-called “Sick Man of Europe.” “The Turk embodies all the lowest attributes in the human race,” the Armenian ranted one evening. “Selfish, brutal, and cruel, he hesitates at nothing. If he thinks he can gain by committing a murder, he will do so.”

The three friends decided to rent a large room where they could all live together. Every evening, they prepared their meals over a little coal stove and talked politics and philosophy long into the night.

Once, Gürdjian brought over an Armenian friend who spoke no English. The conversation turned to American affairs. Allen commented on the infamous Haymarket tragedy in Chicago in which a bomb claimed the lives of seven policemen. As Gürdjian began to translate for his friend, the two suddenly began a shouting match. When they finally calmed down, a mystified Sachtleben asked Gürdjian what all the fuss had been about. “I’m afraid he’s an anarchist,” Gürdjian explained. Taken aback, Sachtleben turned to the man to ask in French if that were true. The Armenian glared back and retorted, “You have plenty of money, why haven’t I?” A stunned Sachtleben confined his advice to his diary: “You had better not come to America or you too might decorate a scaffold someday.”

The Americans also made friends with a young Greek named Basilios Georgiou Kapsambelis whose family had made a fortune in the textile industry. Spotting Sachtleben and his bicycle one afternoon at a café, the Greek approached the American to ask if he could give cycling lessons. Sachtleben laughed at the proposition but agreed to pay the young man a visit later that day.

At his palatial residence, Basilios showed Sachtleben two sparkling new bicycles, a safety and a high-wheeler. The Greek explained that he and his brother had ordered them from England and needed to learn how to ride them. While the American examined the vehicles, a servant handed him a glass of cognac. After taking a few reluctant sips, Sachtleben announced that he would be happy to teach the brothers how to ride the safety. He volunteered his own mount to serve as the second steed. The three promptly headed to the seashore with their wheels, and within half an hour the brothers had mastered the art of cycling.

Vying with Gürdjian and Basilios for the attention of the American cyclists, if not their affection, was a German expatriate named Anton von Gödrich. Formerly an army officer, he had abandoned a diplomatic career to indulge in his favorite pastime: riding his beloved high-wheeler in foreign lands. For the past few years, he had been based in Athens where he founded the city’s first bicycle club.

Sachtleben quickly sized up the diminutive German as a hopeless curmudgeon who “clung to his big wheel when the whole world was turning to the safety.” The American was also put off by Gödrich’s obsession with club life. “He proudly said he was a member of the General Union of Velocipedists, the largest cycling organization in the world,” Sachtleben noted. “When we told him that we didn’t care two cents for any kind of Union his countenance fell.”

Despite their common passion for touring, their philosophies were as disparate as their choice of bicycles. “This fellow, German-like in his thoroughness, started to do every country on a bicycle,” Sachtleben related. “From what I could glean, he was not going in a direct line but jumping around here and there. He had been at it three years and was still unknown in London, the greatest place for cycling in the world. His trip will consume a dozen years at that rate.”

What irked Sachtleben most about the German was his massive ego. After professing surprise that the Americans had not read about him, Gödrich proceeded to monopolize their conversation. “We couldn’t mention a town or city or country where he had not been,” Sachtleben grumbled.

Still, for all his flaws, Gödrich was nothing if not friendly. He insisted that the Americans visit his clubhouse for an evening of entertainment. “It consisted of two small rooms in northern Athens,” Sachtleben reported, “decorated in German fashion as nearly all the members are Germans. Greek wine and German songs and music constituted the program. We drank but little wine and smoked no cigars. Four Greek ladies, two old and two young, were present. The gentlemen had no regard for them, smoking before them with perfect nonchalance. These girls remind one of wooden posts put up for ornament. They are stiff, ill at ease, and never utter a word or smile unless in a whisper between themselves.” The Americans soon found themselves the center of unwanted attention, forced to defend their choice of wheel. “Gödrich had imbued all the members with a love for the high wheel,” Sachtleben recounted. One “thick-skulled German” even insisted: “There’s more fun in the high-wheeler. It is more difficult to learn and when you fall, you fall harder.” Sachtleben resisted the urge to snicker. To him it was obvious which pattern represented the machine of the future.

Compounding their discomfort, Gödrich disparaged their plans to cycle through Turkey come springtime. “Gödrich gave us the most frightful description of the road we were going to follow,” Sachtleben wrote. “We listened as politely as possible while he chattered away. In the first place, the season was bad. The mud would be a foot deep. We would have to swim swollen streams and fight brigands. We would lose our way and a dozen other objections. He concluded that we simply could not do it.”

Finally, at midnight, the beleaguered Americans made their escape. They vowed to ignore Gödrich thereafter. Yet the German would have the last laugh, denouncing the Americans in the German cycling press. “They speak quite boldly about cycling around the world,” he seethed in one article, “but mostly they travel by train and ship. Showmen like these are an insult to true sportsmen.”

The Americans could not, however, easily dismiss the German’s dire warnings about the road through Turkey. They appealed to Gürdjian who knew the country well.

Alas, the Armenian confirmed that the Turkish interior was extremely dangerous and getting worse on account of political upheaval. Fearing that they might “strike Turkey at the worst possible moment,” the cyclists began to consider a safer route through Alexandria, Cairo, Jerusalem, and Baghdad.

In any case, the tourists needed new bicycles. Allen volunteered to go back to London by train to make the purchases. To avoid any potential embarrassment, should he be recognized traveling without his bicycle, he shaved off his mustache, dyed his eyebrows, and donned expensive clothing borrowed from Basilios, complemented by spectacles and a cane.

On the morning of February 4, 1891, the train that would take Allen away steamed into the station. Basilios vigorously shook Allen’s hand. Sachtleben followed suit, fighting back tears. “For the first time in nearly eight months,” he recorded that evening, “Allen and I were to be separated for more than a few hours.”

A month later, Allen returned from London toting two new sturdy Humber bicycles with “cushion” (hollow) tires. Both vehicles, which would in fact be ridden across Asia over the next 18 months, are still intact (Sachtleben’s is held by the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles, Allen’s by the London Science Museum).

With the arrival of spring, the two bade a fond farewell to Athens and headed by steamer to Constantinople with their new wheels and trusty Kodaks. They still were not sure exactly how they would cross the great landmass of Asia. Their route would depend, in large part, on whether Russian authorities granted them permission to enter their territory.

But at least one thing was certain. Despite numerous warnings, they would indeed risk their lives by setting off to pedal 1,000 miles across troubled Turkey. Four years later, Frank Lenz of Pittsburgh would disappear along the same route while trying to complete a similar world tour — prompting Sachtleben’s return as an investigator.