A Tale of Two Annies

This article first appeared in the June 2021 issue of Adventure Cyclist magazine.

“Started Naked. Paul Jones now Clothed in Brown Paper. Left Press Club at 2 AM to Go Round the World. Must Return in a Year with $5,000.” So read a startling headline in the Boston Globe on the eve of Valentine’s Day, 1894. The article went on to recount the sensational saga of “Paul Jones,” who was later exposed as E. C. Pfeiffer, a strapping 27-year-old Harvard graduate and former crew captain.

“The scheme originated one cold evening in the rooms of the Boston Athletic Association,” the Globe elaborated. “Mr. Jones said that a man should be able to make the circuit of the earth by starting without a cent, work his way around, and return with a few thousand in his pockets. Listeners laughed at this rather extravagant statement and declared that such a thing couldn’t be done.” The parties agreed to settle the matter with a $5,000 bet.

Per the terms of his agreement with his fellow clubmen, Jones settled in a room of the Boston Press Club. He divested himself of all his clothing to start with absolutely nothing but his wits and grit. Jones earned his first funds by charging every visiting reporter a one-cent entrance fee, then used the proceeds to send out for paper and paste. After making himself a suit with those materials, he ventured out into the night to start his peculiar journey.

Ten days later, after Jones had made his way to New York City, primarily by shining boots and lecturing, the Boston Post broke a related story. “Jones has a Rival,” the headline ran. “A Plucky Woman to turn Globe Trotter.” As the paper explained: “The eccentricity of Paul Jones has become contagious and a woman intends to demonstrate that she, too, can go around the world, starting penniless and returning with a cool $5,000.”

Indeed, the “projectors” of this copycat scheme made only two small concessions to the female “Paul Jones.” First, she would be spared the need to start naked, although “at the time of starting, the woman will have only the clothing she wears and not a penny to her name.” The second adjustment was that she would have an additional three months to complete her circuit because “it takes a woman longer to travel than a man.” But her objective was the same as Jones’s and she was to start on the first of May. “From that time on,” read the Post, “she must begin to hustle for dollars, which she hopes to earn by lecturing as she travels. Dress reform will be the principal topic.”

And just who were these projectors? The Post alluded to a committee headed by Albert Reeder, a Boston physician. “When Paul Jones’s episode was at fever heat,” the paper explained, a group of supporters of the “New Woman” resolved to find and enlist an adventurer who was fit, competent, and motivated enough to replicate Jones’s feat, and possibly even “go him one better.”

And whom did they select for this herculean task? “Her globe-trotting name will be Mme. Marguerite Leland.” The Post teased: “When she gets ready to start, her real name will be made known.” In the meantime, the paper offered this profile: “Mme. Leland is about 27 years old, married, her husband being a businessman in Boston. She lives in Melrose and is quite a linguist, being able to speak four languages fluently. She is also an honorary member of the Women’s Press Association.”

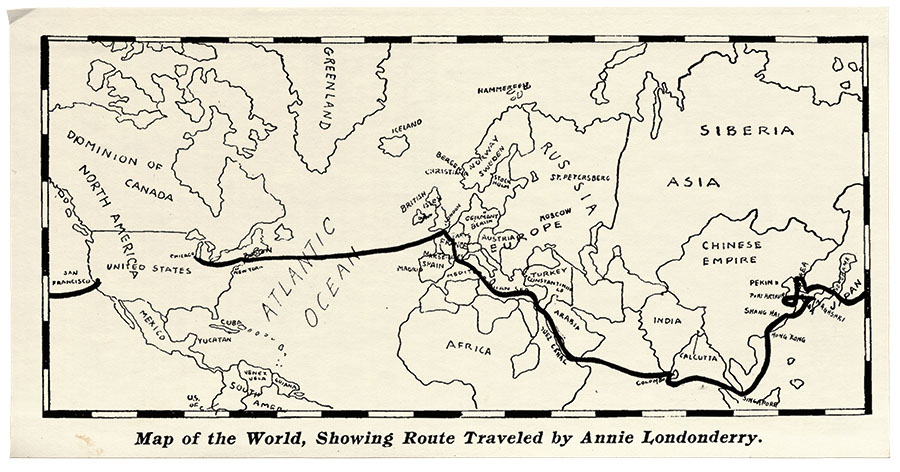

As for her itinerary, the Post affirmed, “she will make her way first towards San Francisco, where she will take a steamer for the Sandwich Islands before starting for Japan and China. The rest of the route includes British India, up the Nile to Cairo, Italy, France, England to Boston again.” And naturally, being a “New Woman” living amid the great bicycle boom, she would occasionally rely on the two-wheeler to save time and money. “Her plan is to purchase a bicycle out of the funds she earns at the start,” the paper affirmed, “and with this machine make a portion of the journey.”

Another report a week later specified that Leland would start from Malden, just south of her hometown of Melrose. By this point, the bicycle had assumed a more significant role in the plan as Leland would reportedly “do the trick on a bike.” Meanwhile, Pfeiffer was arrested in Springfield, Massachusetts, for prior debts and confessed that there had been no bet after all. Leland’s backers recast her as a female “Frank Lenz,” a young man from Pittsburgh who was in the midst of a round-the-world bicycle trip.

Leland didn’t leave on May 1 as planned. In fact, she didn’t present herself at all until nearly two months later. On June 25, she appeared not in Malden but rather on the steps of the Massachusetts Statehouse in Boston surrounded by a few friends and dignitaries. Although the governor sent his last-minute apologies for his no-show, a representative of the Pope Manufacturing Company delivered Leland a 40-pound Columbia bicycle with a drop frame to accommodate her skirt.

Leland dramatically turned her pockets inside-out to prove that she had no money on her, as she recounted the “bet” backstory: a wealthy “woman hater” had wagered $20,000 that she would fail in her mission. In contrast, her backers had put up $10,000 and would reward her with a like sum upon successful completion of her goal. Leland also announced that she would henceforth be known as “Annie Londonderry,” thanks to a $100 advertising fee paid by the Londonderry Lithia Springs Company, a bottler in Nashua, New Hampshire.

The next day, the Boston papers finally revealed the identity of Miss Leland-turned-Londonderry: Annie (née Cohen) Kopchovsky, a Jewish immigrant from Latvia. Surprisingly, according to the reports, she did not look particularly athletic, being short and “slight in build.” She was invariably described as a brunette with lively dark eyes. One paper observed that “she is in no way afflicted by the goldenness of silence.” Another concluded that she was “evidently of nervous temperament,” noting “in addition to the revolver she rides upon, she carries one for protection against tramps.”

Nor did Annie answer Leland’s pre-ride profile. She was 23 (not 27). She lived in Boston’s gritty West End (not the tony suburb of Melrose). Her husband, Max, was a peddler (hardly a businessman). She knew no foreign languages and she had no track record in publishing, let alone a distinguished career.

Perhaps the most surprising revelation of all was that Annie was the mother of three children under the age of six. One bystander jokingly suggested that she should get a bicycle built for four so that she could haul them all along with her on her tour, but Annie shot back that she had trouble enough cycling on her own. “Her husband is perfectly willing that she should make the journey,” one reporter affirmed, “otherwise she would not have undertaken it.”

Why did the Annie Londonderry who set off on this quest appear so differently from the original Marguerite Leland? While previous biographers have asserted that Leland had fluffed up her résumé like a recent graduate, trying to present someone older and more fit for the task than her appearance might suggest, new information has come to light to challenge that theory. Whether it was cold feet, something sinister, or the generous promotion of a well-connected woman looking to help out a mom in need of an opportunity, this seems like a tale of two Annies. Whoever Marguerite Leland was or wasn’t, Annie “Londonderry” Kopchovsky capitalized on a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to make a better life for herself and her family.

Even her relationship with her bicycle questions her very identity. Although she started with a Columbia, and a Columbia representative was on hand, there is little evidence of any partnership. Columbia ads never mentioned Annie, and she never praised the bicycle. This suggests that Leland may have made the original arrangements with Columbia, and Annie Kopchovksy inherited the bike but not a true sponsorship. Is this the same reason the governor canceled his speech at the last minute?

Annie’s next moves were surprisingly erratic for someone who had supposedly been planning the trip for at least four months. After the ceremony, Annie headed straight to the nearby studio of Mrs. Ober-Towne, a “woman photographer” described as Annie’s “chief encourager.” Together they produced calling cards that Annie would sell along the way. After earning $30 for her two hours of work, Annie slept in her own bed.

Not until a few days later did Annie cycle out of Boston, with no fanfare. Instead of heading west to Chicago, she rode south to Providence. Once in New York, Annie settled in with a friend and spent nearly the entire month of July in the metropolis — a surprisingly long lull for someone who was allegedly battling the clock. But she apparently needed the “down” time to line up a few more sponsors whose ads she stitched into a new, more comfortable cycling suit that she had designed herself.

On Friday, July 28, braving sweltering heat, Annie staged yet another official departure, this time from New York’s City Hall. Several hundred, including a host of animated street urchins, gave her a boisterous send-off. She then “rapidly wheeled her way over the asphalt to Broadway, and nimbly evaded cable cars, trucks and express wagons [before being] swallowed up in the crowd of vehicles.”

Several papers mentioned that Annie now had an advance-man who traveled ahead of her to make overnight arrangements, alert the press of her imminent arrival, and possibly carry some of her gear. In one account, he was identified as Fred Gallager, an Irish journalist and boxing promoter. But it appears that he did not stay with Annie for long, at which point she relied exclusively on volunteer escorts for ride support.

That evening she arrived in Yonkers, and the next day she gave a women-only lecture on the “Beautification of Women.” When asked how she intended to support herself, she responded “I have dozens of plans, and if the worst comes to worst, I shall sell soap.” And evidently her fundraising in New York City had paid off. “I have $1,900 in drafts payable in six months,” Annie boasted, “which I will receive for advertising New York merchants.”

Annie was expected to reach Albany, some 140 miles up the Hudson, in two days (she reportedly averaged about 65 miles a day). But she did not show up there until nearly three weeks later. Had she discretely taken a train back to New York City to complete a few more business deals? She apparently offered no explanation for the delay, and she proceeded nonchalantly to visit the state capitol, praising its architecture. A few days later, at the close of August, she reached Buffalo, spending the night at a reverend’s home. The next day, she called on the office of a local paper and insisted she was well on the way to raising $5,000.

But however well things may have been going from a financial perspective, her geographical progress was clearly lagging. After more than two months on the road, she was barely 500 miles west of Boston. Reaching Erie, Pennsylvania, in early September, she hinted that her heavy bicycle was weighing her down. Had she a 19-pound race model instead, she told reporters. she could surely cover a mile in two minutes.

Chicago, the epicenter of the American cycling industry, was still another 500 miles to her west, and it hardly seemed braced to welcome her with open arms. The Referee groused: “Mlle Londonderry — whose correct name ends with ski or sky — is bearing down upon us. She ought to be caged, and it is not to the credit of any bicycle, saddle, or tire maker to aid her in beating her way around the country. Cyclists along her route would be doing the cause a favor by ignoring her completely.”

On September 24, Annie finally reached Chicago. She kept a brave face, telling reporters that after a couple of weeks of rest, she would “tour through the South leisurely and then go to San Francisco to embark for the Orient.” But a week or so later, she woke up to reality. She decided she would scrap her world tour, get a racing bicycle, and try to cycle to New York in record time, before heading home to Boston.

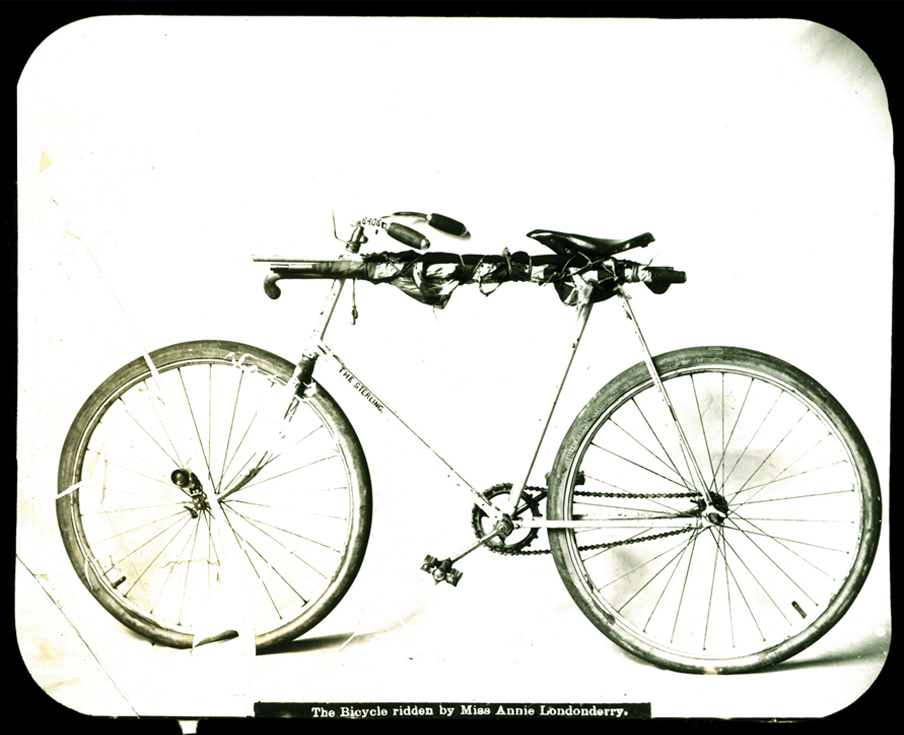

But as the New York–based Wheel and Cycling Trade Review reported, good fortune intervened. “The Sterling Cycling Works [of Chicago] have become interested in the young woman’s venture,” the magazine reported, “and as a result her plans have undergone considerable change. Her heavy dropped framed wheel has been exchanged for a twenty-pound diamond framed Sterling, enameled white, and on Sunday next [October 14] Miss Londonderry will retrace her way to New York. Here she will embark for France.”

Annie’s third official departure, this time from Chicago’s City Hall, drew another hundred spectators, including adoring members of the Ladies’ Cycling Club. “All along the route down Michigan Avenue,” the Inter-Ocean reported, “unattached cyclists joined the procession until the number of escorts reached several hundred, a number going all the way to Pullman (about 12 miles) and several going as far as Hammond (25 miles south, across the Indiana state line).”

As Peter Zheutlin recounts in his Kopchovsky biography, Annie not only reversed direction after acquiring her Sterling, she also completely remade herself. For starters, she discarded her split skirt in favor of bloomers so she could straddle the diamond frame. A journalist in Waterloo, Indiana, pronounced her attire “shocking.” And Annie did not stop there: she soon decided simply to wear men’s trousers.

She also adopted a whole new attitude. No longer would she be content to merely plod along on her clunker. She was now ready to pick up the pace and complete her mission. She planned to return to Chicago within a year so as to claim a full global circuit by bicycle. That would also allow her to return to Boston by train before the 15-month deadline (supposedly she was not obligated to travel overland exclusively by bicycle).

Annie’s “second wind” also seems to have emboldened her to stretch her tall tales even further and to embroider ever more her genuine accomplishments. Among other falsehoods, she began to tell reporters that she was a Harvard medical student.

As popular as she had become, this bolder Annie invited growing criticism. Many openly questioned “the bet.” Others maligned her integrity. The Waterloo journalist noted with disdain that Annie had purchased a number of “souvenir pins” at a local store, reselling them to townfolk for a quarter each — twice what she had paid for them.

After a pleasant sail on the luxurious Tourraine, Annie landed in Le Havre in early December 1894, ready for a fresh start. She had reached “ground zero” of the cycling world. Just months before, French cyclists had inaugurated a memorial to Pierre and Ernest Michaux, declaring the father-and-son tandem the inventors and developers of the original “boneshaker” bicycle of the 1860s. After being overshadowed for two decades by its British counterpart, the French cycle industry was at last thriving once again, and the country enjoyed a culture of bicycle racing and touring second to none. Annie was a most welcome arrival.

In her first French interview, Annie alluded to Lenz, who was now reportedly missing in turbulent Turkey. “Miss Londonderry’s object is to prove that what a man failed to perform, a woman can do,” the reporter relayed, adding that Annie intended to progress “principally by my own exertion” though she was counting especially on assistance from women. “Understand that I do not come to beg money,” Annie stressed, “but I would like women to show interest in my tour.”

Plans to enter a five-day contest at the Velodrome d’Hiver (the Winter Velodrome) fell through, but she found work at the Salon du Cycle, the massive end-of-the year trade show. There she handed out flyers at the stand of the British cycle maker. She got a great deal of press, mostly favorable, and raised a significant sum.

On New Year’s Eve, Annie and a few escorts started off in frigid weather toward Marseilles, 500 miles to the south. It would be the only significant ride she would make outside the U.S., but it was a memorable one. She was mobbed and interviewed all along the route. By the time she boarded her steamer on January 20, 1895, thousands of cheering fans assembled at the pier to see her off.

Over the next three months, her ship docked at Alexandria, Colombo, Singapore, Saigon, Hong Kong, Shanghai, Nagasaki, and Kobe. She cycled only briefly during those stops, though she continued to give interviews to the local press. In mid-March 1895, Annie landed in San Francisco to face a swarm of reporters. She took a southern route to El Paso and through Arizona and New Mexico. She then headed north to Chicago, the endpoint of her cycling journey. Throughout her western swing, Annie continued to enjoy celebrity status. She constantly met up with reporters and adoring fans. In Las Vegas, New Mexico, she was reportedly “lionized” and “jocularly referred to as Miss Bostonberry.”

Annie’s reputation, however, began to suffer irreparable damage. Although she continued to endure genuine hardships, suffering several serious accidents, she increasingly exaggerated her cycling exploits as well as her misadventures. “The young lady may be going round the world on a wheel all right,” scoffed one writer in Lordsburg, New Mexico, “but most of her traveling in Arizona and New Mexico appears to be done on a car wheel instead of one of the pneumatic variety.”

Even more dubious and objectionable were her wild tales of foreign lands. She spoke in vivid detail about touring the Holy Land, braving the jungles of India, and surviving the Sino-Japanese war. But little if any of that was true.

“Who is Annie Londonderry?” thundered the Colorado Chieftain that August, in anticipation of her arrival in Pueblo. “Some of the marvelous tales that she has uttered elsewhere have wafted into the Chieftain office,” the paper elaborated, “and it was determined to look her up a bit.” After all, the editor reasoned, if she had truly tripped over dead bodies on a Chinese battlefield while dodging bullets, she surely would have been interviewed extensively on the matter when she reached San Francisco.

The initial results of the editor’s inquiry were not favorable to Annie. A return telegram from the Boston Herald, where she claimed to have worked, read “not known here.” And he got an earful from an editor in Las Cruces, who said he had never met “a greater romancer” than Annie, adding that any colleagues who had taken her seriously “have more good nature than good sense.”

He went on: “She said that she was the daughter of an English lord, that her father was a physician in Boston, that she lived in an elegant home, that she earned $5,000 a year off her literary work, and yet she told all this stuff with a slang that a Bowery boy might envy. She said she rode her wheel through India, Burma, China, and Siberia, that she hunted and killed a tiger, was attacked by Chinese bandits, some of whom she killed. Her own pamphlet, printed in California, gives the lie to all her stories, for it plainly says that she traveled from Marseilles to San Francisco by steamer with only a short side-trip ashore in Japan.”

On September 12, 1895, Annie rolled into Chicago, claiming to have completed a 10,000-mile “round-the-world” cycle tour. Like most of her claims throughout this voyage it was a dubious assertion, given that she had cycled only a few hundred miles abroad, and in total about half the miles she claimed.

Annie nonetheless declared victory, insisting she had indeed raised $5,000 en route (and quite possibly she had). She promptly took a train to Boston, arriving precisely 15 months from the day she had appeared before the Statehouse. Allegedly, she collected her $10,000 reward, and presumably her young, struggling family began to enjoy a better life. Sadly though, Annie’s hopes to parlay her adventure into a career in journalism failed. She and Max relocated to New York City and had one more child together. Annie “Londonderry” Kopchovsky died in obscurity in 1947.

Lost in much of the controversy and misinformation surrounding her round-the-world journey is the fact that Annie did indeed accomplish a remarkable physical and mental feat, even if she had not been the original choice for a female “Paul Jones.” But more importantly, she delivered a powerful statement for her times and for posterity. As she put it, “A woman can do anything any man can do.”