Water, Sand & Ice

This article first appeared in the July 2005 issue of Adventure Cyclist magazine.

Looking back as far as I can remember, I always wanted to travel. My first expedition was planned in my pram, a long crawl to and through a gap in the garden hedge. My frantic mother found me atop a neighbour’s rockery some time later. For a second try, I used a red pedal car to visit friends the other side of town, which didn’t go down too well with Father. The first was hard on the knees, the second on the backside. He had a hard hand! Father and I never did see eye to eye on my travel aspirations. Later I found two wheels were better than four and still think so when I see the present chaos in our cities.

The long growing-up business created a frustrating delay in my childhood plans to be an explorer. If I didn’t hurry, there might be nothing left to explore! To the detriment of my general education, I spent hours absorbing the discoveries of the early navigators in the polar regions as well as their routes to the cannibal-populated South Sea Islands. How I hoped there might still be the odd cannibal around. The result? At least I did well in geography.

A further setback was enforced military service, which I spent happily enough in the Royal Air Force in Arabia, India, and East Africa. Consequently, it wasn’t until 1963 that I was ready to see the world independently.

In this era of supersonic airliners and orbiting satellites, it is often said the globe is shrinking. I’d argue, “Not for those attempting to circle it on a bicycle.” My projected two-year tour did, in fact, take 10.

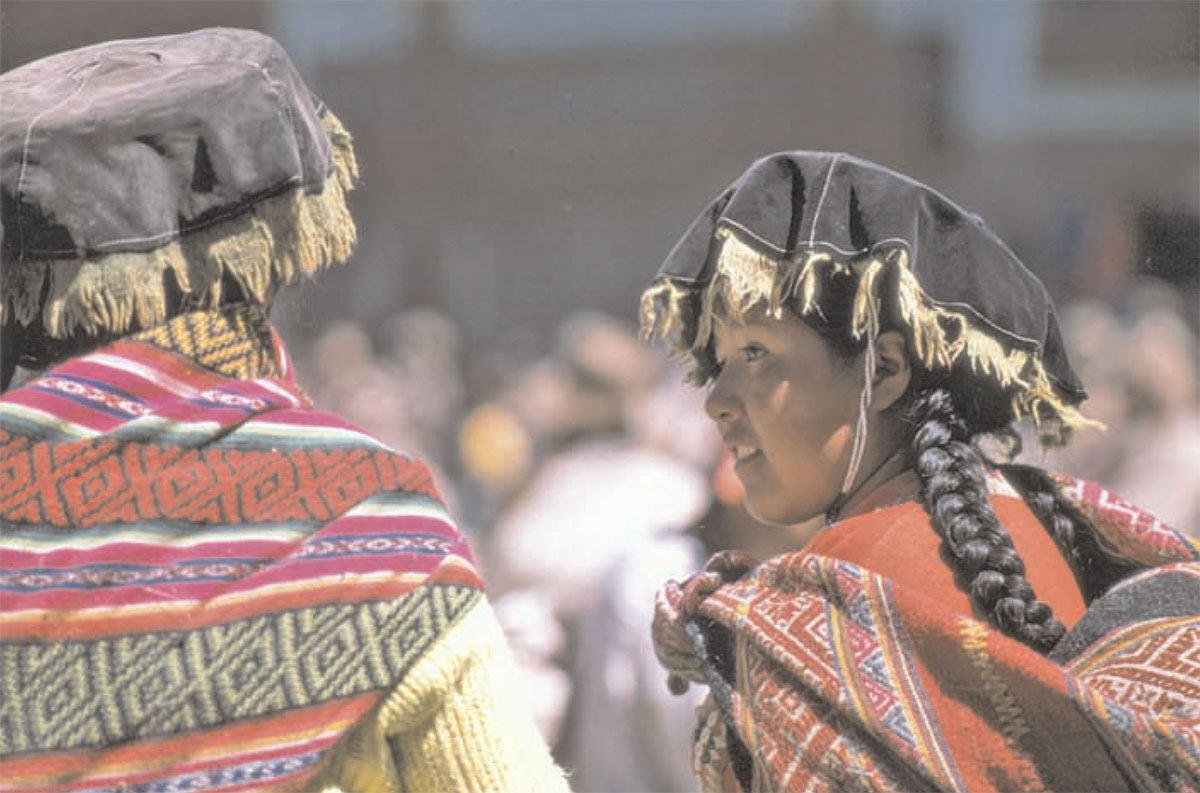

It has been suggested there are quicker or more comfortable ways to do it, but speed was never one of the criteria. Comfort? There are admittedly disadvantages in this respect, for in riding across the pampas or penetrating a jungle, I get in such a worn and unwashed state my own mother wouldn’t recognise me. However, this in itself acts to my advantage. Arriving in a village tired, hungry, and dirty often gains hospitality never offered to those in a better state of appearance or health. Pressed to rest a while in an Iban longhouse, to spend Christmas with an Eskimo princess, or to sit out a blizzard in a traditional Korean home, I have been introduced to the very ways of life I have come to experience.

During those tenderfoot years of wandering, I reached Asia via Canada and Alaska. It was in Japan amongst her volcanoes, shrines, and kimono-girdled girls that I finally abandoned all ideas of keeping to a time schedule. Thus began a scintillating stay in Southeast Asia followed by two years as a Youth Hostel Association warden in New Zealand. Familiar with the Middle East, I opted for new horizons on the way home.

Cape Horn to Alaska had always been on the agenda ever since reading of an attempt to travel there by amphibious vehicle, the first to try it before the PanAmerican Highway had even been completed. The knowledge that a ship would sail to South America in eight months’ time was the catalyst. I’d go! The distance was great, over 18,000 miles with the diversions I had in mind, and an additional challenge was the gap in the highway system at the joining of the continents, Panama’s Darien Gap, and the more difficult Atrato Swamp in Colombia. The Panamanian section has been driven by much winching and the use of rivers, but the swamp had remained an impregnable barrier.

I gained two companions, and the British/New Zealand Cape Horn to Alaska Cycling Expedition was born and nurtured around a cosy youth hostel fire. Although neither of my kiwi friends were cyclists, the carrot that drew them was my intention to tackle that uncrossed swamp and the jungle beyond. All other expeditions before and since have used the river system — as do the Indians — to avoid the swamp, but this involves a huge road and river detour. We ambitiously wanted to be the first to use the direct route, which the eventual road was designated to follow.

Our expedition sailed for Punta Arenas in southern Chile and we rode north from Cape Horn in early 1970. With the leg from the Horn behind us, we had reached our obstacle.

With help from the British Embassy — which, as it couldn’t legally stop us, gave up and assisted — and the Colombian Army’s issue of hammocks and snake serum, we were as prepared as we could be and entered the jungle in a nervous state of excitement tinged with apprehension. Others had failed. Why? We were about to find out. If supplies ran out before the halfway point, we could always retreat! Couldn’t we?

After nearly four weeks of effort, we did run very low on food — only damp oatmeal left. Cutting and sloshing our way through the growth on a compass bearing on the final stage to the Rio Atrato — beyond lay the border hills at Panama — our optimistic expectation of the necessary two kilometers a day was to be dashed. We measured our first cut: 400 meters! Redoubling our efforts on the second day: 700 meters. Our morale plummeted. If conditions failed to improve, should we obey our brains and get out or respond to our hearts and give it a go? The considerable effort we’d made in riding from the Horn was not easy to throw away.

We continued until retreat was no longer an option. In our passage forward and the ferrying of our gear, we’d developed a trench that was too deep to return along. Down to two tablespoons of oatmeal twice a day, we were weakening.

By our calculations, we must be quite near the river and the island village of Traversia. In desperation, we pushed John up a tree to look. He couldn’t see the river but did spot a hut. We were puzzled for we knew of nobody living in that waterlogged locality. We took a fresh bearing and changed course. That night, we lay uneasily in damp hammocks, listening to our noisily grumbling guts, thinking of nothing but food.

My hammock supports — a pair of very anaemic palm trunks — gradually bowed under my weight and gently lowered my backside into the murky water. Like the dog too lazy to roll off the thorn, I was too exhausted to fix it. Gary broke our thoughts when he said he thought he’d heard a cow bellowing. We all listened intently but concluded he had been dreaming and had been back on his New Zealand farm.

Then, unmistakenly, above the whine of the insects, we heard the staccato sound of an outboard motor banging to life. The noise of the boat’s wake and the sweet sound of that motor faded rapidly into the watery distance. It had sounded so near, but it took us two more days of struggle to reach the bank, and as a compliment to our navigation, or just plain luck, there, 400 meters away, was our hut, one of a cluster named Traversia. We eventually attracted attention by waving our bikes in the air and were canoed over to crawl up the mud steps to stand on dry land for the first time in 26 days. A scarecrow would have scorned the rotten rags we peeled off. Our physical appearance would have brought tears to a Spanish inquisitor. We were torn, bloody, and haggard, but how good it felt to be alive!

Having rested, we set off into the hills to enter Panama. In Travels with Rosinante, the French author employed guides and porters in an attempt to reach the Cuna Indian village of Paya. He gave up and boated back and out. Having crossed the swamp, we found this stage relatively easy and reached Paya independently. I took exception to a passage from his book: “They looked for unnecessary difficulties. Everybody admits (not us!) that crossing the Darien Gap overland includes the necessity of a boat trip up or down the Atrato River.” The crux of our expedition was to cross the Darien Gap using the most direct route. We didn’t have to look for difficulties; they were in the way to be overcome. At the cost of severe immersion foot, we achieved a first, the first complete overland crossing by any means, power, foot, or dolphin-assisted. I was so wet, I’ve not had to have a bath since, and you should see my webbed feet.

In 1971, we still had to negotiate over 200 miles of jungle to reach Panama City. Now, I believe, a road takes the traveller almost as far as Colombia and the Atrato River, where boatmen are more than willing to take passengers to the Caribbean port of Turbo. What a shame! That final Panamanian jungle journey was difficult, but the beauty of it will never leave my memory. Stick a road through anywhere and it contaminates the natural order of existence of both flora and fauna. The human inhabitants are supposed to gain, but I wonder how much they lose.

On reaching Panama City, both my companions quit the tour, and I continued alone to Alaska.

Then, in 1973, as it was when I reached Alaska from Newfoundland, Canada, at the beginning of my world tour, Circle City was as far north as one could get on the highway system. That was, until the pipeline support road was built to Prudoe Bay. It was inevitable that I should return to finally reach the Arctic Ocean. I was allowed, under escort, to ride down to the East Dock. There, 30 years after dipping my toes in Tierra del Fuego’s Antarctic waters, I completed the ritual on the northern coast of Alaska. The sea was just as chilly but not my welcome home.

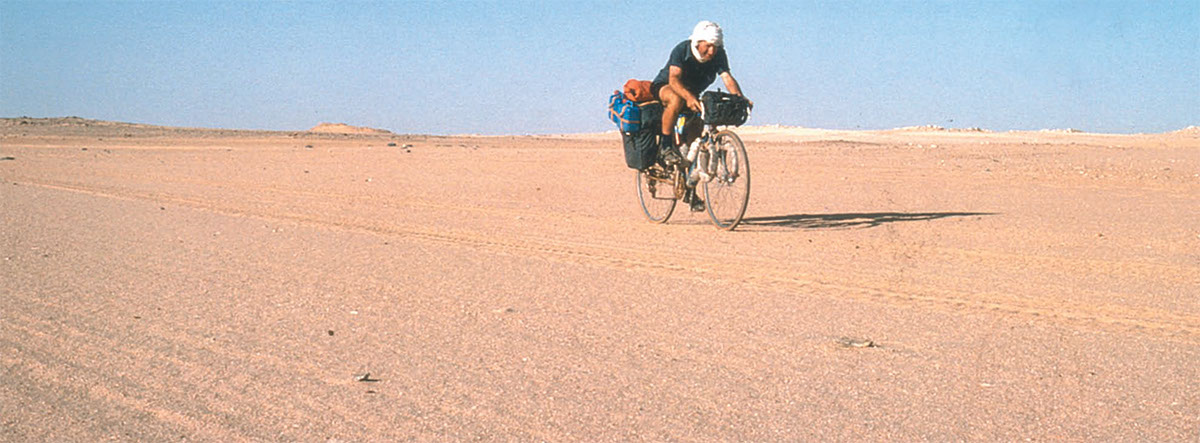

In 1963, I’d been granted a year’s leave of absence from my job in Devon. Now, 10 years later, I hadn’t the nerve or inclination to try and reclaim it so I had to find something else to do. I chose to write to earn my crust for I was already selling my tales. For more material, Norway’s North Cape to Cape Town appealed. Crossing the Sahara Desert would give me something to get my literary teeth into and might cure my webbed feet.

The news circulated. One of Mother’s elderly friends apprehended me in the street and wagged her finger at me disapprovingly. “Your poor, poor mother. She worries about you so much.” I could see her visualizing the dangers. “What will you do if you meet a lion?” she asked. I explained that it was very much up to the lion. There was nothing much I could do if it was hungry but strip and offer it salt, I said with a deadpan face. The explanation didn’t go down too well, and her opinion of me as a “nice young man” tumbled as she tut-tutted on her way.

A few months later, my sick joke came back to haunt me. The old lady needn’t have worried for I’d not meet a lion now. I was lost in the Sahara.

Fully topped up, I could carry enough water to last me for three days. On average, I’d been resupplied by the curious passengers of passing vehicles every other day, but traffic had dried up and on Day Five I was down to two pints. I couldn’t sleep for thinking I’d not survive the morrow, so I decided to walk through the night with the help of the stars.

At dawn, I laid the bike down, and as my compass had been stolen, used the rising sun as a navigational aid, walking directly towards it. During the night I knew I’d drift off the main track — a five-mile width of criss-cross wheel marks — if I didn’t find it to the east, I’d use my shadow — westwards. There was no sign of it on either side; with a sinking feeling I knew I’d broken all the cardinal desert rules and was now lost. Compounding the situation, I couldn’t even locate the bike and those final two pints of water. Time had passed and the sun was no longer a red orange ball but shimmered with the intensity of an acetylene torch. My physical condition was not yet critical, but I had no hope of rescue. I just needed somewhere out of the sun to die in. The sand was burning through the soles of my shoes, and it was barely 10:00 AM.

There was a certain irony that during the night I’d blundered into the bushfringed edge of the desert and I was nearly through. The mirage effect made these growths tantalisingly tall, offering the shade I craved. As I approached, each “haven” shrank back to its true squat size, offering no shade at all, not even an apology.

I was done for. I couldn’t complain. I’d taken one risk too many. But “Oh, God, help me,” I whispered, more from my mind than my throat. What instinct drew me to turn around I know not. Shielding my eyes with a shaking palm, I intently squinted into the sun. I stared with incredulous disbelief at what must surely have been a hallucination. A small biblically clothed figure leading a baby camel was approaching me. Was I dead already? I checked and wasn’t. I’d stumbled into a band of nomadic Touaregs. I’d live!

Many years later, having toured the Falklands, I found myself in the right place at the right time to voyage to the “Continent of Ice.”

Ship’s Log

“We landed on the Antarctic Continent in spectacular sunshine to a reception of Gentoo and Adelie penguins. Never had they seen anything quite like it — an Englishman, on a bicycle. Ian Hibell, who had travelled on his bike on every other continent, wasn’t going to miss the chance to ride here, and the penguins were quite confused to see someone managing to get around so quickly.”

Professor Molchanov — 21 March 1998

No, I didn’t frighten the penguins. They gathered around quickly, one obviously explaining the merits of gearing to his mates.

I didn’t reach the South Pole either, but what a buzz that short tour gave me.